The Town Devoted to Philosophy

In February 2016, in the company of Raphaële and two monks from Shechen, I was able for the first time to visit the Larung Gar academy of philosophy, which had long been off-limits to foreigners. Eventually, foreign nationals were allowed to visit but not to stay, so we had to leave before nightfall.

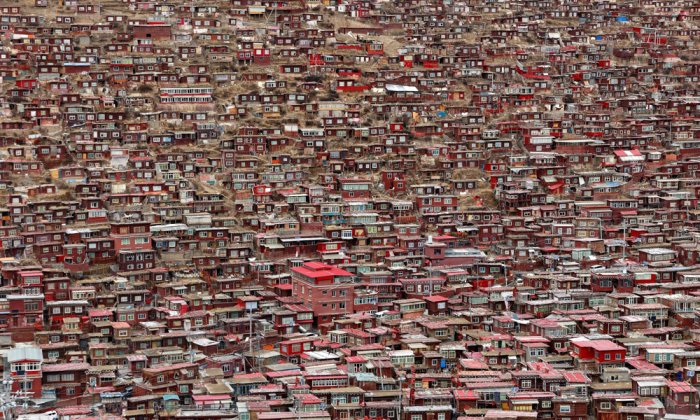

Around the bend of a small pass, a unique panorama lay open before us: the largest Buddhist university in history, apart from Nalanda and Vikramashila, famed institutions that thrived in India 2,000 years ago! The Larung Gar academy of philosophy, located in Kham, at an altitude of 14,000 feet, was home to more than 10,000 monks and nuns (who made up the majority of the monastic population), as well as hundreds of lay students. From nearby hilltops, the magnitude of this citadel of the mind is evident. The vista is an immense mosaic of row upon row of tiny student houses covering the valley’s three slopes.

Our visit coincided with a prayer week in which the entire community participated. Every day, a nun and a monk took turns leading prayers that took place in the two main temples rising from the midst of the residential neighborhoods. Amplified by loudspeakers, the voice of the nun leading the prayer that day so dominated the chanting of thousands of participants that everyone was able to sing in unison. When we climbed to the top of one of the prayer-flag-covered hills that overlook the valley, and sat for a while on a large boulder, I asked myself, “Where else in the world is there a valley where nothing can be heard all day long, for an entire week, but songs of the Dharma filling space with their serene harmony?”

In 1980, having studied under the best scholars of his time, Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok and a handful of his students founded this academy of philosophy, Larung Gar, in an uninhabited valley near the little town of Serthar, in southeastern Golok. From 1960 to 1980, the most intense period of Chinese repression, Jigme Phuntsok had led the life of a nomad, practicing in mountain hermitages. His charisma and the high quality of teaching at the Larung Gar philosophical academy very soon attracted a growing number of students, coming to form a small city, populated not only by Tibetans but also by hundreds of Chinese, who came to receive teachings in their own language.

In 1989, Jigme Phuntsok went to India at the invitation of Penor Rinpoche, founder of the largest Nyingmapa philosophical college on the Indian subcontinent, with 3,000 monks and nuns as students. In 1990, he met the 14th Dalai Lama in Dharamshala, then sought out Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Delhi. He prostrated three times before Khyentse Rinpoche, and one of his monks later told me that it was the first time he had ever seen him prostrate before any lama other than the Dalai Lama. Jigme Phuntsok also went on pilgrimage to Bhutan, where he exchanged teachings with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

On his return to Tibet, he refused to denounce the Dalai Lama, as demanded by the Chinese, which caused him serious problems. The government henceforth denied him all permission to travel. In 2001, several thousand members of the Chinese army brutally stormed Larung Gar academy and bulldozed a third of its residences. This was just one of the many arbitrary actions taken by the Chinese government against the vitality and resilience of Buddhist culture. Thousands of students were expelled and the lodgings of 3,000 nuns were destroyed in order to reduce the population of scholars and students. From that point on, access was strictly forbidden to foreigners as the authorities sought to obstruct any witnesses and testimony to the destruction and abuses carried out there. While some people managed to visit in secret, I could not — despite my desire to see this spiritual landmark for myself — take the risk of putting my friends at Shechen Monastery in danger or undermining our humanitarian projects, which were already very challenging, given all the restrictions imposed by the government.

Jigme Phuntsok died in 2004, at the age of 70, leaving the philosophical academy leaderless but no less thriving in spiritual and philosophical terms.

At Larung Gar, there are no fewer than 600 khenpos, learned “doctors of philosophy” who have completed a minimum of 12 years of study and teach the basic texts of Buddhism to classes of 30 to 40 students. The lack of academic and clerical hierarchy is a trademark of the academy’s operations. While certain khenpos — such as Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö and Khenpo Sodargye, to name but two — may be highly respected in Tibet and China, the administration is strictly horizontal at Larung Gar, and they have no claim to special treatment or elevated rank. The most eminent khenpos live in the same two-room cabins that are assigned to everyone. At major ceremonies, the song master sits on a small throne, needing to remain visible and audible while leading the prayers, while the other members of the monastic community sit in the order in which they arrived and, not, as in the case of most monasteries, according to their seniority or preeminence.

I met Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö in Chengdu in 2014; he, alongside Khenpo Sodargye, is the senior khenpo and spiritual successor to Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok. He was 50-ish, and I was struck by the simple manner and affability of that great scholar and engaged thinker who, among other things, has made a great contribution to the cause of vegetarianism in Tibet. He cites the Great Parinirvana Sutra, in which the Buddha affirms, “Eating meat destroys the attitude of great compassion.” The vegetarian diet has always been popular in Tibet and was promoted by a great number of past masters, although it has never been predominant, no doubt because of the climate (agricultural cultivation is impossible above 12,000 feet and the winters are very long and especially harsh there). Every year, Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö and his Chinese students release into the lakes and rivers more than a million live fish, purchased wholesale, that were raised for human consumption.

Over the course of a few months in 2015 and early 2016, the restrictions for foreigners to visit Larung Gar were relaxed, but entry was again forbidden by summer of the same year. The government had instead decided to launch a new phase of destruction of the monastic residences. With that radical measure instituted in the summer of 2016, only those who had been born in the Serthar district were allowed to study in the academic valley; the others were ordered to return to their homelands. To facilitate their ease of access and their “regulation” of the academy’s expansion, the Chinese also cut broad roads through the residential neighborhoods. It must be said that this had certain benefits; the truth is, the close proximity of residences was the cause of many fires. In fact, while we stood at the top of the hill, a small fire broke out near the edge of a neighborhood where many dwellings had been torn down in 2001. Within minutes, 200 or 300 monks were shuttling back and forth in lines on the hillside with buckets of water. Thanks to their diligence and energy, they managed to extinguish the fire.

The legacy of Tibetan Buddhist culture is under severe threat, but despite all adversities, its spiritual transmission remains intact to this day.

We agreed among ourselves that, in the face of a systematic policy of persecution and the elimination of monks and monastic institutions, Larung Gar was an extraordinary example of the resilience of Buddhism and the iron resolve of the Tibetans in that long-persecuted land. Awed and moved by the amazing scenes we had witnessed in the university — unique of its kind in the world, with its 10,000 philosophy students, their prayers rising from the valley to fill the air — we left Larung Gar, a monument to the Tibetan philosophical tradition, with heavy hearts.

On my many journeys to Tibet between 1985 and 2017, I had developed a deep attachment to the Land of Snows. It is the place where I feel most at ease and most powerfully inspired to grow, study, and practice. I am by nature drawn to high altitudes, so the cold and high plateaus of Tibet are an ideal living environment. There are so many other sublime landscapes on our planet Earth, but in Tibet these places of great beauty are imbued with the subtle but palpable presence of my spiritual teachers, the men and women, hermits, monks, nuns, and lay practitioners who, from Padmasambhava’s day to ours, have lived in these physically and spiritually special places.

The legacy of Tibetan Buddhist culture is under severe threat, but despite all adversities, its spiritual transmission remains intact to this day. We can only hope with all our hearts that it is able yet again to overcome any obstacles it encounters under the yoke of a totalitarian regime.

Matthieu Ricard is a Buddhist monk, humanitarian, writer, photographer, doctor in cellular genetics, and the French interpreter for the Dalai Lama. He is the author of, among other books, “Notebooks of a Wandering Monk,” from which this article is excerpted. All of his royalties are donated to Karuna-Shechen, the humanitarian association he created 22 years ago, which benefits more than 450,000 underprivileged people every year in India, Nepal, and Tibet.