Grieving the Passenger Pigeon Into Existence Again

In February 2012, a group of scientists, environmental thinkers, and science writers gathered at Harvard Medical School. They were not there to talk about medicine, but rather about bringing the dead back to life. The daylong meeting, sponsored by the Long Now Foundation, explored the technical feasibility and potential pitfalls of using genetic engineering to resurrect the extinct passenger pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius.

Since its launch in 1996, the Long Now Foundation has been attempting to instill long-term thinking in modern culture through projects like the Clock of the Long Now (a clock designed to run 10,000 years without intervention) and the Long Bet Project (which takes bets on predictions for conditions no less than two years into the future). Before the group gathered to talk about the passenger pigeon, it had already shown an interest in the potential extinction of human language: Its Rosetta Project produced an engraved metal disk holding 14,000 pages of information and has collected texts and recordings in over 2,500 languages to preserve them for the future. The passenger pigeon meeting would kick off the Long Now Foundation’s interest in nonhuman extinction, later formalized as a wildlife conservation organization called Revive & Restore.

The meeting centered on rapidly advancing genetic technologies that allow the recovery of ancient DNA sequences, as well as detailed genome editing. The combination of these two advancements would mean that DNA of long-dead species could be sequenced and then remade by modifying the DNA of existing species. George Church, a genomic engineer at Harvard Medical School who served as the on-site host, stressed the high degree of precision in genome-editing techniques and proposed that the band-tail pigeon Patagioenas fasciata could be used as the starting genome for making a new passenger pigeon.

The drama of the pigeon’s extinction seemed to be enough justification to make de-extinction an appropriate response.

Although other candidates for revival were mentioned as potential alternates, no one questioned why the passenger pigeon was being discussed in the first place. The drama of the pigeon’s extinction seemed to be enough justification to make de-extinction an appropriate response. The pigeon was lost, and perhaps it could be found.

In the history of the passenger pigeon, people interested in pigeons, their extinction, and their potential revival have tended to follow Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s model of the emotional stages of experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Denial: A Land Filled with Pigeons

The sheer number of passenger pigeons made deep impressions on early Americans. The passenger pigeon was a migratory bird moving across vast swaths of North America, with wintering grounds as far south as what are now Florida and Texas and summer breeding grounds in the Midwestern states up to Ontario. It was primarily a woodland bird, with regular roosting in oak, beech, and chestnut stands. Mark Catesby’s early 18th-century work on the birds of the southern states described the passenger pigeon coming to the region in “incredible Numbers; insomuch that in some places where they roost (which they do on one another’s Backs) they often break down the limbs of Oaks with their weight, and leave their Dung some Inches thick under the Trees they roost on.” When John James Audubon, who published an exquisite drawing of a passenger pigeon pair in his life-size Birds of America series, described the passenger pigeon in 1831, their numbers amazed him. Describing one migration event he witnessed in 1813 in Ohio, Audubon wrote that “the air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse, the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose. … The Pigeons were still passing in undiminished numbers, and continued to do so for three days in succession.” Their numbers were “immense beyond conception.” The grandeur of the pigeon flocks evoked feelings of wonder and the sublime.

The pigeons in these vast and seemingly unending flocks were remarkable, but not out of place. The new American continent, which was still early in its colonization in the first half of the 1800s, was understood as a boundless source of natural resources. The Midwest, where the pigeons were most numerous, featured fertile land that had been parceled out to farmers along the grid. Commercial agriculture centered on grain turned the Midwest into America’s breadbasket. From the mid-1800s, new train lines increased the connections between the resource-abundant Midwest and West with the financial centers in the East, making it faster and easier to move commodities.

The abundance of the passenger pigeon led to appropriation of the bird as a natural resource. Even in 1731, Catesby recorded that from New England south to Philadelphia, a great number of pigeons were shot or knocked off their roosting places during their migrations. For Audubon, it made sense that when the flocks came through the area, “the banks of the Ohio were crowded with men and boys” who shot down sacks full of the birds so that “for a week or more, the population fed on no other flesh than that of Pigeons.” The pigeons were shipped by the barrel to urban centers like New York for consumption by the urban poor. Although the kill rates were high, commentators in the mid-1800s saw no lessening of the pigeon numbers. Audubon stressed that only deforestation, not hunting, would bring about any reduction in the number of passenger pigeons.

Yet the passenger pigeons did die out. By 1894, the local bird expert Oscar Byrd Warren of Palmer, Michigan, was worried about the pigeon because he hadn’t seen any in a few years. Over the next four years, he solicited reports about passenger pigeon sightings far and wide, but the birds were scarcely seen. No conclusions could be made about why the wild pigeons were no longer common. There was an underlying assumption that though the bird’s numbers had greatly decreased, they were not necessarily on the verge of extinction; they must have just gone somewhere else.

Anger: What Has Become of the Wild Pigeons?

In 1907, W. B. Mershon published “The Passenger Pigeon,” a collection of recollections and publications about the bird. He stated that his intent was “to throw light on the oft-repeated query, ‘What has become of the wild pigeons?’” This was a question that puzzled many from the last decade of the 19th century. Passenger pigeons, which were itinerant birds that followed no set migratory route or schedule, had tended to show up in a given locality sporadically every few years. But by the time Mershon wrote, observers had compared notes and found that none of them had seen the pigeons. The emotional reaction to the recognition of the pigeon’s loss was anger, one of the significant stages in the grieving process.

Mershon’s introduction to his compiled text claimed that the passenger pigeon was extinct at the time of the writing (in 1907), and the blame was to be placed squarely on Americans, who were “wasteful” and always in “pursuit of the almighty dollar.” The passenger pigeon is depicted as a creature that was minding its own business at home when invaders from the outside came in. The pigeons in their brooding places were natural and belonged there; the hunters with their telegraph lines and rifles were unnatural and undesirable.

Anger about the slaughter of the pigeon reached a pinnacle with “Our Vanishing Wild Life,” published by William Hornaday in 1913. Hornaday — who was the chief taxidermist at the United States National Museum (later renamed the Smithsonian), then director of the Bronx Zoological Park for 30 years, and a key early wildlife conservation figure — had been heavily involved in setting up the American Bison Society to save the iconic American animal after it had become extinct in the wild. The pigeon and buffalo were often linked in discourse about extinction, with both as allegories of the dangers of capitalism and the pigeon’s extinction serving as a potential outcome for the bison. Hornaday’s book, which carried the subtitle “Its Extermination and Preservation,” and which featured a short summary of the “long and shameful story” of the passenger pigeon’s decline and extinction, was intended as “a loud alarm, to present the facts in very strong language, backed up by irrefutable statistics and by photographs which tell no lies, to establish the law and enforce it if needs be with a bludgeon,” according to New York Zoological Society President Henry Fairfield Osborn, who wrote the book’s foreword. On the first page of Hornaday’s preface, he stressed that he was “appalled” at North America’s “wild-life slaughter” and “a restless, resistless desire to ‘kill, kill!’”

Bargaining: Attempts to Resuscitate a Dying Breed

In the last decade of the 1800s, there were some attempts to help the passenger pigeon numbers recover. To start, a few groups proposed hunting moratoriums or permanent laws banning hunting of particular types. An early legislative attempt at controlling passenger pigeon hunting led the way for the eventual adoption in 1900 of the U.S. Lacey Act, which was the first significant legislation aimed at the preservation of game and wild birds. But all this was too late to reverse the damage done to the passenger pigeon numbers.

In a more intensive intervention, some maintained that wild pigeons could recover through breeding in captivity. This was the tactic taken successfully for the American bison (known as buffalo) and European bison (also called visent). The American variety had been reduced in number in the United States to less than 100 free ranging plus 200 in Yellowstone National Park by 1889. Private herds, as well as those owned by the federal government, became the breeding stock that were released onto public lands in the first decade of the 1900s. The European bison suffered an even more dramatic decline, with no existing wild population in 1927. Zoological garden populations that had been gathered at the beginning of the 1900s were actively bred through the International Society for Protection of European Bison in the 1920s, and 12 animals became the ancestors of all wild visent today.

Passenger pigeons were kept by two breeders, in addition to a few zoological gardens, when the precipitous decline was realized. David Whittaker of Milwaukee had a personal aviary with passenger pigeons as “pet birds.” He had acquired two pairs in 1888, although the older pair soon died. He successfully bred the younger pair in captivity, so that when ornithologist Ruthven Deane visited in March 1896, there were about 15 birds there. Soon after Deane’s visit, which he documented in The Auk, the flock was purchased by Charles Otis Whitman. Whitman, who became a professor of zoology at the University of Chicago in 1892, worked extensively with breeding pigeons, raising over 30 species of pigeon in coops at his home. He was particularly interested in scientific questions of genetic inheritance, as well as the viability of cross-species breeds. He established a pigeon breeding center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, which he visited each summer.

By 1906, Whitman’s flock was a meager five individuals, “the last representatives of a species around whose disappearance mystery and fable will always gather.”

Whitman’s early successes at passenger pigeon breeding were hailed by Boston Evening Transcript in 1901 as a “revival of this almost extinct species.” But the attempt ultimately failed: By 1906, Whitman’s flock was a meager five individuals, “the last representatives of a species around whose disappearance mystery and fable will always gather,” as one ornithologist wrote. None of Whitman’s birds would ever be released into the wild.

As the flocks in captivity dwindled to nothing, ornithologists attempted to mobilize a dramatic search for any wild pigeons that could still be conserved. At the 1910 annual meeting of the American Ornithologists Union (AOU), a reward of $300 was offered for information leading to a pair of undisturbed nesting passenger pigeons, and others issued similar rewards for identification of living birds in particular states. The rewards applied only to live birds because the idea was to protect the living animals and any nests.

The search was on. In November 1910, Clifton Fremont Hodge, a professor of biology at Clark University who spoke at the AOU meeting, reported on the “search of the American continent for this lost species.” In an unexpected interpretation of the reward, Hodge had begun receiving nests by post because the newspapers had carefully stated that the rewards were based on nests, not dead birds; fortunately, these had all been mourning dove nests. There had been no evidence of passenger pigeons, but Hodge claimed that “negative evidence is proverbially inconclusive” and still held out hope that a couple of seasons would be needed to decide whether or not to abandon the search. His reason for “prolonging the misery” of the search was simply that he “could not let go,” he wrote in his investigation. The grief would not loosen its grip on him. He recognized the futility of the search, suspecting that “the worst fears of American naturalists were about to be confirmed and that we are ‘in at the death’ of the finest race of pigeons the world has produced.”

The search was continued into 1911, but no confirmed passenger pigeons were found. Hodge remarked that the great irony was that many of the sightings came along with reports that the birds were killed, even though the rewards specifically stipulated that the birds were not to be harmed: “The nightmare of the whole situation has been that the last survivors of this great species were being ignorantly shot off,” he wrote in exasperation. Despite this sentiment, Hodge reissued the rewards for 1912. None were claimed. Hodge’s grief shows a transition from a bargaining phase, in which hope still held out, to a state of misery and depression.

Depression: Pigeons and a Profound Sense of Loss

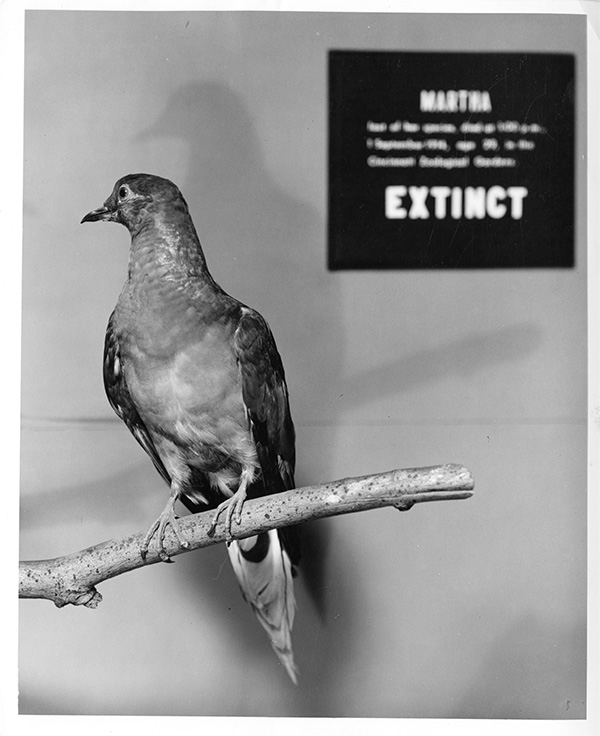

On September 1, 1914, in the Cincinnati zoological gardens, the last known passenger pigeon died. Martha had spent her whole life in captivity. She had lived alone at the zoo since 1910, when she lost her mate, George (the pair had been named after the first president of the United States, George Washington, and his wife, Martha). They had never successfully produced offspring.

Although the imminent death of the entire race of passenger pigeons engendered a narrative of anger, the final passing of this one pigeon brought out a new narrative structured around loss. Martha had been in poor health for several years, and at the end of August 1914 her death was imminent. The day before her death, the Washington Times issued an article, reprinted in other national papers, that began like a hospital visit to a dying friend: “In the Cincinnati zoological gardens there is dying today, if the bird is not already dead by the time this appears in print, the last known passenger pigeon in the world.” Lamenting the loss of the last was paramount. The Cincinnati Enquirer announced her death on September 2 this way: “‘Martha’ is dead. In one great respect she resembled Chincatgook, the ‘Last of the Mohicans,’ for she was the last of the Passenger Pigeons.” Her death was a “calamity,” according to a later commentator. All these news articles portray the passenger pigeon’s passing as an event that should be mourned by all.

When she was found dead, her body was put on ice and shipped to the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. R. W. Shufeldt performed a detailed autopsy as part of the taxidermy preparations of the body. Shufeldt documented in detail the work to skin the body and provide a scientific anatomical description, taking numerous photographs along the way. It appeared that Martha had suffered from severe internal bleeding, with her liver and intestines disintegrating before the autopsy. Although he attempted to write a distant, objective, scientific description of the anatomical features of passenger pigeons, Shufeldt was moved by his work on this particular bird. His description of his work when he got to the heart betrays his true feelings: “I therefore did not further dissect the heart, preferring to preserve it in its entirety, — perhaps somewhat influenced by sentimental reasons, as the heart of the last ‘Blue Pigeon’ that the world will ever see alive. With the final throb of that heart, still another bird became extinct for all time, — the last representative of countless millions and unnumbered generations of its kind practically exterminated through man’s agency.” The profound sense of loss felt by Shufeldt is evident here in an otherwise scientifically neutral text.

In 1932, the Smithsonian issued a report declaring the formal extinction of the bird and put the mounted body of Martha on display. Martha’s skin was made into a taxidermy mount and was displayed in the National Museum’s Bird Hall, then moved to the Birds of the World exhibit. The Smithsonian report noted frequent claims of passenger pigeon sightings, but these were always either mourning doves or band-tailed pigeons. The report dismissed theories that continued to pop up claiming the birds had either relocated south or were all wiped out in a catastrophic weather event. The extinction of the passenger pigeon led to communal grief. Loss was poignantly foregrounded in the creation of memorials and monuments to the extinct passenger pigeon in the post–World War II period.

In 1976, the U.S. government issued a pamphlet titled “A Passing in Cincinnati, September 1, 1914” to commemorate the passenger pigeon’s extinction. The pamphlet is set up as a funerary commemoration for Martha, including a graphic style that makes each page look like a gravestone. The text announcing the death of Martha from the Cincinnati Enquirer starts the work, followed by her portrait. After retelling the species extinction story, the text returns to Martha herself and her body as monument. Twice she flew after death — once in 1966, when she was sent to the San Diego Zoological Society’s Golden Jubilee Conservation Conference, and again in 1974, when she appeared in Cincinnati as part of the launch of the Passenger Pigeon Memorial Fund to restore the birdhouse where she (as well as the last Carolina parakeet, who is often forgotten) died. The pamphlet is a text written as grieving at a graveside. “A Passing in Cincinnati” assumes that grief for the pigeon will be permanent, just as Martha would be on permanent display.

Martha was not, however, kept on display permanently at the Smithsonian. Her body was put into storage in 1999 when the Birds of the World exhibit was shut down to make room for a new Hall of Mammals. She would not appear again in the public eye until 2014, to mark the centenary of her death and the extinction of the passenger pigeon. By the time she made her centenary appearance, talk had already begun about her not being the last.

Acceptance? De-extinction and Longing for Passenger Pigeon 2.0

The February 2012 Long Now Foundation meeting at Harvard took place amid these stories of the passenger pigeon that had passed from this world. Building on the grief narrative, the participants in the meeting were instigating a new story: one that shooed away acceptance of the loss and returned to a bargaining phase. The loss of the pigeon had led to a longing for bringing the pigeon back, and this was a longing that might be possible to realize through new techniques. They wanted to move forward by turning back the clock.

The Revive & Restore project rapidly expanded its reach with a second meeting in October 2012, which tripled the number of participants, before hitting a high point with a TEDxDeExtinction event hosted by National Geographic in Washington, DC, in March 2013. National Geographic featured de-extinction as the cover story of its monthly magazine, and the TEDx event was streamed live on the internet. The program was chock-full of de-extinction proponents, who discussed the potential de-extinction candidate species, the technical possibilities of genetic technologies, and histories of conservation efforts that brought nearly extinct species out of danger. There were presentations spouting words of caution, but these were few and far between.

Passenger pigeons turned into a de-extinction poster child, along with the mammoth. Two of the talks at the TEDx event were specifically on the passenger pigeon, and the species featured prominently in the National Geographic coverage. Press coverage of the event often reproduced drawings of passenger pigeons, such as Audubon’s watercolor, and highlighted the passenger pigeon case. From the perspective of the Long Now Foundation, the passenger pigeon had always been at the center of de-extinction and the related new subdiscipline called resurrection biology.

Ben Novak, the scientist leading the work in Revive & Restore’s flagship project “The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback,” has stated that bringing back the passenger pigeon is “about the pigeon’s place in the forests of tomorrow. To know how to proceed we must explore the past. My thoughts in the pursuit of de-extinction are to the great flocks of passenger pigeons and how they shaped the forest.” The millions of birds certainly would have been significant distributors of seeds and consumers of forest resources. In his view, conservation is at “a turning point that the de-extinction of the passenger pigeon can sway towards the value of life, just as the extinction of the passenger pigeon did so powerfully a century ago.” That flip of conservation is something that Stewart Brand, who founded the Long Now Foundation, has argued is a primary reason to use genetics to bring extinct species back to life: “That something as irreversible and final as extinction might be reversed is a stunning realization. The imagination soars. Just the thought of mammoths and passenger pigeons alive again invokes the awe and wonder that drives all conservation at its deepest level.”

This is a radically different framing for recovering the passenger pigeon than experienced earlier in the story of its loss. The emotional basis for the intervention was still grief at the loss of the pigeon, but rather than accepting the passenger pigeon’s fate as already made, the Revive & Restore practitioners have essentially entered a new bargaining phase based on hope and wonder.

Revive & Restore may, however, have entered a devil’s bargain in its attempt to resurrect the passenger pigeon as a mode of dealing with collective grief. First, while the project may end up with an animal to release, there is little reason to believe that the pigeon will be successful in recolonizing the Midwest. Most of the land has been modified beyond recognition by agriculture, and those humans that inhabit the bird’s original territory would not likely share the land. Even in 1970 on the 56th anniversary of the passenger pigeon’s extinction, Texas columnist Marjorie Adams, who had a syndicated newspaper series called “Bird World,” commented: “We of today decry the slaughter that brought the extinction of the elegant and tasty passenger pigeon. Yet if we had the pigeon returned to us is anyone foolhardy enough to believe that agricultural American would tolerate its existence in such numbers for long?” Second, there is the potential that the social meaning and significance of the passenger pigeon resurrection will focus on the fantastical, science-fiction qualities of the project rather than the biological or ecological science and its implications.

The 2012 workshop on the resurrection of the passenger pigeon had been aptly titled “Forward to the Past.” The new genetic technology was the forward-looking aspect, whereas the longing for the return of the bird that motivated so much of the work was grounded in the past. The grief of losing this species that had once numbered in the billions has permeated the discourse from Hornaday to Brand. Humans commenting on the loss of the passenger pigeon do so time and time again using the emotional framework of grief. They believe that this bird lost through extinction belonged fundamentally to the American landscape. The Revive & Restore project promises that perhaps the lost bird may again be found through its resurrection.

Dolly Jørgensen is a historian of the environment and technology and an environmental humanities scholar. She is the author of “The Medieval Pig” (Boydell & Brewer) and “Recovering Lost Species in the Modern Age,” from which this article is adapted.