Bicycle 'Landseeërs': The 19th-Century Cyclists Who Rediscovered the American Landscape

In 1894, a group of Baltimore wheelmen formed an association called The Thirteen Cyclers, hoping to explore as much new territory as possible given the topography of the surrounding countryside and the time at members’ disposal. The group’s travels are recorded in two small, handwritten volumes titled “Route Book” and “Book of Runs”; together, they are an archive that revels in discovery — and one noticeably different from the records of many other bicycle clubs, because the entries contain few references to social activities or reports of racing. Charles Rhodes served as captain, and his year-ending missive, written shortly before the club’s anniversary ride in April 1895, became a proclamation of the club’s founding purpose. Noting that they had covered much ground that had been little known to the cycling fraternity during the preceding year, Rhodes outlined his ambitious objectives for the coming year, an itinerary that stretched across most of Maryland and steered toward locations in Pennsylvania, reaching as far as Steelton and Gettysburg.

Rhodes observed that the greatest difficulty for touring in new districts was to find suitable points to obtain meals, but on more than one occasion the group also had trouble finding its way, venturing along cow paths of dubious outcome, into thick woods, across fields of high weeds, or through deep pockets of sand. Although some narratives capture the appeal of special outings — for instance, a moonlight ride “of the old kind” to Ridgeville — or point to notable land features, such as a windmill-like signal for a ferry crossing on the Little Choptank River, with red blades for passengers and white for teams, the books are most valuable as unadorned impressions of travel by bicycle during the late 19th century, best read with a willingness to tarry if one hopes to imagine those journeys. Possessing a heightened awareness of their surroundings and stirred by the compositional elements inherent in those landscapes, these Baltimore wheelmen had become discerning landseeërs.

As commonly used, the word seer describes a person or mystic who is gifted with profound spiritual insight or one for whom divine revelations are made known through visions. However, a few notable writers have altered the word’s spelling to seeër in order to avoid the customary interpretations. Instead, they have used the term to apply to persons whose sense of sight is penetrating and who employ that capacity to achieve understanding, whether through contemplation or imagination. For example, while discussing the romantic writing of Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson described Scott as “a great daydreamer, a seeër of fit and beautiful and humorous visions.”

Bicycle landseeërs often travel close to home, suggesting that the word’s meaning should encompass a newly found familiarity with the nearby unknown.

The word landseeër is particularly apt for late 19th-century bicyclists, who, having mastered a newly engineered means of independence, awaken to their environs with a sense of anticipation and are able to observe those settings from a fresh perspective. Often, bicycle landseeërs travel close to home, suggesting that the word’s meaning should encompass not only exotic travel experiences but also a newly found familiarity with the nearby unknown, where much has been overlooked. Charles Pratt, one of the founding members of the League of American Wheelmen (LAW) in 1880 and a frequent contributor to cycling’s touring literature, reminded his readers that although distance lends enchantment, true enchantments are not all distant: “Ten to one you, Reader, unless you be a wheelman, do not know your own county.”

As landseeërs, bicyclists observe what others are unable to see, but the explanation is hardly mystical. In his thoughtful little book titled “Outside Lies Magic,” landscape historian John Stilgoe notices that pedestrians moving past a picket fence see only narrow segments of features located behind the fence and are unable to visualize a complete picture. However, a bicyclist, moving effortlessly at just the right speed, mentally assembles those glimpses rapidly enough to create a composite view to remarkable effect. Yet Stilgoe could extend his observation beyond just picket fences. The ability to move at a distinct pace endows cyclists with the ability to record mental images of various land features, recalling and connecting them in creative ways and forming visual prospects that remain invisible to others — panoramas unseen by those whose views are confined to fleeting glances that offer little insight about cultural imprints on the land. Today, bicycling’s landseeërs can spot the traces of history that others disregard in our built and cultural environments and can offer imaginative and fitting visions for reclaiming those forgotten places.

The vanishing remnants of 19th-century bicycling heritage are as good a place as any to start that process of discovery. For roughly two decades, from 1880 to 1900, bicycles and bicyclists shaped and reshaped American social, cultural, economic, and industrial history; introduced an independent and dependable means of overland travel; propelled a campaign to improve the nation’s pitiful network of roads; influenced the appearance of cities in subtle ways; swayed park planners; and set into motion the modern machine and engineering technology essential to the development of automobiles and airplanes.

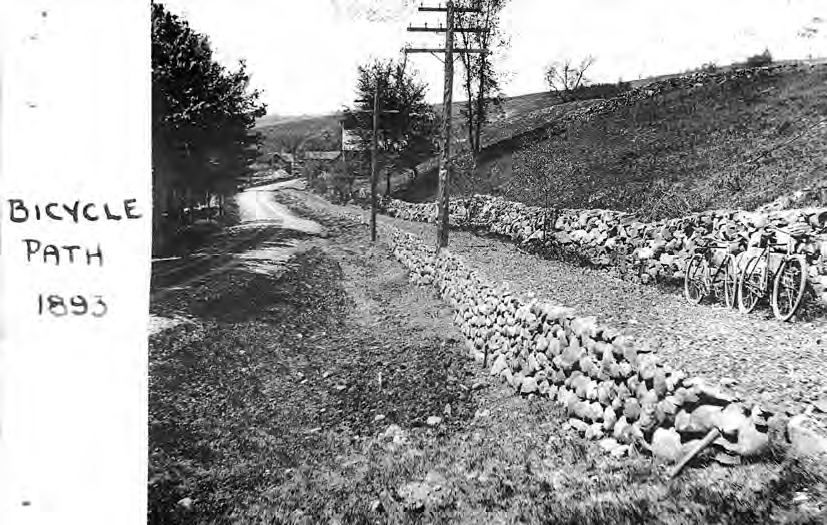

Wheelmen and wheelwomen also assembled a substantial and today greatly underutilized body of geographical literature, illustration, photography, and vivid descriptions of American places, becoming in the process some of country’s keenest observers of suburban and rural landscapes — and skillful landseeërs. These cyclists also financed and built a surprisingly extensive network of bicycle paths to satisfy their exploratory impulses — more than 2,000 miles in New York State alone — and accomplished that feat in less than a decade, a remarkably short time when one considers today’s short, five- or six-mile projects that can consume years of planning or debate and cost enormous sums.

Unfortunately, today we can point to very few landmarks or monuments that nurture the public’s collective memory of cyclists’ important contributions. Clearly, those disciplines that speak for our built and cultural environments should correct this poor record of recognition accorded to cycling heritage.

With those thoughts in mind, I set about the task of turning the pages of as many of cycling’s journals as possible — and there are a great number — in an effort to trace the direction of cyclists’ 19th- and early-20th-century wanderings; to seek the vestiges, landmarks, imprints, or traces of cyclists’ former journeys; and where possible to reclaim the paths, wheelways, or thin bicycle traces that once formed a vast system of dendritic-like travel corridors that made country riding possible. Rather than beaten trails through wild or unknown regions, however, those narrow, tire-worn passages instead signal the start of searches through a different type of uncharted terrain: the urban, suburban, and rural locales where bicycles can function safely, both as vehicles for recreation and as a means of transportation. Charting a course for those investigations, or taking one’s trace, is as uncertain today as it was a century ago.

Establishing manageable geographic boundaries for the project also became necessary, and I have been traveling across fourteen states — New England’s six states, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Ohio, Indiana, and a small portion of Kentucky — ever since the project began about 12 years ago. Temporally, the period of study begins shortly before the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, at which the American public first inspected high-wheel bicycles, a stately English invention, and concludes with the onset of World War II, when a reviving interest in bicycles and bicycle paths — pointing to a modern era — is forestalled by that conflict.

The resulting work [“Old Wheelways”] seeks a better acquaintance among landscape historians — who ponder the subtle weave of place, time, and public memory on the land — and bicycle historians, who study the far-reaching influences of one of humankind’s great inventions. From that acquaintance, hopefully, a fruitful dialogue will emerge and diffuse among those who investigate a wide range of closely related disciplines: the cultural geographer who interprets the meaning evident in the layered traces of human activity on the land; the historical geographer or urban historian who seeks to reconstruct and understand the ever-shifting edges separating suburban and rural environments during the closing decades of the 19th century; the urban planner or historic preservationist who today seeks to reclaim those same lands, now densely urban and often forsaken; the odologist (landscape historian John Brinkerhoff Jackson’s word) who studies the irrepressible transformation of our roads from connective corridors into complex public spaces; the ecologist who is intent upon assessing the changes caused by human interaction with the environment; the historian of tourism who unravels the complex role of travel in shaping modern society; or the enlightened transportation engineer who must transform concept into a practical physical form.

Although many portions of this study are deeply grounded in bicycle history, the point of view is always aligned to emphasize the ways that bicycles have shaped American landscapes and to record impressions of those places. That outlook has governed the overall organization of the work and the development of the various historic contexts that illuminate the scarce remnants of bicycle history on the land. The first chapter, Awheel, introduces the principal and related disciplines to one another.

Thematically, the obvious ties to travel, the importance of bicycles to mobility, and the closely related roles of cyclists as both geographic explorers and path builders — the former providing a partial context for the latter — all help to unify the separate chapters, as do the many connections to American places, and so the bicycle becomes a vehicle capable of crossing the numerous disciplines that touch American landscape-related studies. Those themes traverse time as well as distance, and today’s cyclists can exercise the skills inherited from their 19th-century brethren, becoming landseeërs who can reclaim neglected places or path builders who devise useful routes for urban, suburban, and country riding. One of the most distressing aspects of the history of bicycle path building from the late 19th century is that those early campaigns offer a prologue to nearly every obstacle faced by those who are engaged in the building of bicycle paths and bicycle lanes today. Although more than a century has elapsed, we are no closer to resolving the conflict overuse of public roads by bicycles and other vehicles. Automobiles are only the current — and most dangerous — vehicles on that long list.

Remarkably, some of the creative ideas that cyclists proposed for resolving those conflicts, such as travel ways that combined two very different but compatible types of transportation (trolleys and bicycles), remain relevant today. Those nineteenth-century plans could be adapted to parkways designed for alternative means of transportation — light rail, bicycles, and pedestrians — with each travelway carefully separated by grade, berms, bridges, landscaping or other design features but nevertheless engineered into a fully integrated transportation corridor that also incorporates worthy cultural or natural resources into the daily travel experience: our parkways of the future.

Robert L. McCullough is Professor of Historic Preservation at the University of Vermont and the author of, among other books, “Old Wheelways: Traces of Bicycle History on the Land,” from which this article is excerpted.