A Prehistory of Scientific Racism

In his book “Critique of Black Reason,” philosopher Achille Mbembe writes that whiteness is, “in many ways, a fantasy produced by the European imagination, one that the West has worked hard to naturalize and universalize.” It is a fantasy long in the making. Categorizing and ascribing meaning to difference is a common human trait; we often need to categorize to get by and make sense of the world around us. Sometimes this classification is harmless, and sometimes not. Many ancient texts, for instance, spoke of and ascribed difference to peoples, but did not racialize. It is only with the so-called Age of Exploration, when Europeans reached the western hemisphere, or extended their reach and power deeper into Africa or Asia, that the conditions for a racialized social structure were fully in place.

What would become what we can now recognize as racial formation initially took the language of theology for its model. One particularly common model for arranging beings in the world were cosmic hierarchies, sometimes called a scala naturae (ladder of nature) or the “Great Chain of Being.” These ladders or chains envisioned all creation as connected in a hierarchy from the lowest to the highest forms of being, frequently with God on top after the rise of Christianity.

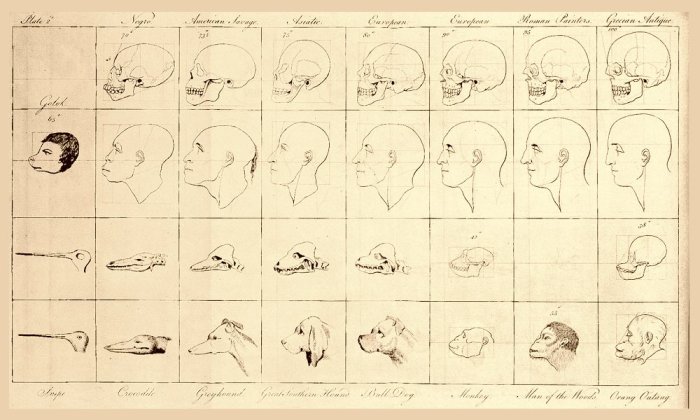

Attested in antiquity, as early as in the philosophy of Aristotle (384–322 BC), they were topics of much debate throughout the Middle Ages and into early modernity. The scalae were often ordered on the level of species. They rarely included racial classifications before the 1600s, when racial thinking entered so-called Western consciousness to stay. Early racial scalae, like those of economist and statistician William Petty (1676) or anatomist Edward Tyson (1699), didn’t garner much attention, but by the time the aptly named physician Charles White offered his white supremacist “An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter” in 1799, racial classification was a welcome tool for those who wanted to motivate the violent conquest of people, land, and resources.

The essentialism of racial thinking took long to develop. Ancient Greeks, Romans, and others displayed varieties of xenophobia, but almost always with an “escape hatch” in conversion or assimilation. Slow movements toward essentialism in prejudices about European Jewry and Black Africans took place over centuries. While anti-Judaism had been part and parcel of Christianity almost from its inception, it wasn’t until the 12th and 13th centuries that some began to speak about an insurmountable difference between Jews and Gentiles. And although the association of the color black with evil has long roots, it didn’t translate everywhere into anti-Black sentiment. Spanish anti-Judaism started to include ideas about the purity of blood (limpieza de sangre) in the 14th and 15th centuries, framed in terms of whether someone was Christian or not, rather than in terms of white and nonwhite, but it stands as a historical “segue between the religious intolerance of the Middle Ages and the naturalistic racism of the modern era,” writes historian and author George M. Fredrickson, in its incipient biologization of difference. Similarly, while it was never universally accepted, the so-called curse of Ham gradually connected Black Africans with Noah’s son Ham, who was cursed by his father to be a servant. The curse was the basis for centuries of debate about the legitimacy of enslaving Black people; some used it to motivate enslavement, and others to oppose it.

Death followed wherever Europeans went, at the barrel of a gun, but also through disease, starvation, and abusive labor practices.

With the advent of settler colonialism around the turn of the 16th century, something else had to take the place of religious language, not least because slavery sat awkwardly next to Christian universalist claims about the unlimited possibility of salvation through Jesus. The so-called discovery of lands previously unknown to Europeans was quickly followed by exploitation, appropriation, and domination. Death followed wherever Europeans went, at the barrel of a gun, but also through disease, starvation, and abusive labor practices.

While the word itself wouldn’t be coined until 1944, European colonialism was a genocidal project: Indigenous American populations came close to extermination after 1492; the Guanches of the Canary Islands were exterminated between 1478 and 1541; and the native Tasmanians were similarly destroyed between 1803 and 1876. Those who survived colonization were often forcibly moved from ancestral lands, such as in the Swedish colonization of Sápmi starting with the introduction there of silver mining in 1635 and culminating in 1919 with forced relocations lasting into the early 1930s. Many peoples were moved again when the lands reserved for them turned out to be valuable to colonizers after all, as happened to Aboriginal Australians until at least the 1950s, the Lakota Sioux after gold was discovered in South Dakota’s Black Hills in 1874, or Indigenous populations in the southwestern United States during the series of forced displacements between 1830 and 1850 known as the Trail of Tears.

New rationalizations were needed to motivate nation building and rapid expansion of world trade, and justify the colonial expansion, exploitation, expulsion, and extermination of Indigenous populations necessary for the profitability of these projects. European encounters with people unfamiliar to them led to questions about whether everyone could be considered part of the same “family of man” and soon thereafter, for example, the moral affordances of enslaving some people.

The so-called Enlightenment also focused on ideals of freedom, natural rights, and equality — rhetorics difficult to reconcile with oppression and subjugation. Distinctions between Europeans of different nationalities, or “Europeans” as an imagined supranational grouping, and their Others were manufactured, producing hierarchies designed to order and motivate ideas of human superiority and inferiority. Through racialization, physical characteristics became the basis for social positioning, and ideas about those characteristics were tied to supposed mental, social, moral, and intellectual traits, among others. These folk understandings of difference were then used to inform policy, law, and social organization. It is in this mix of social and economic structures along with the significations and representations of differences between groups of human beings, often on the basis of skin color, that the “master category” of race would be created, with Europe and thus whiteness at its center.

One of the most thoroughgoing early embraces of racial thinking took place in England’s North American colonies around the turn of the 18th century. The use of unfree labor has a long history. Slavery appears in ancient sources like the Bible or Code of Hammurabi (ca. 18th century BCE). The monocultural mass plantation of sugar in Europe and tobacco in British America were both based largely on forms of enslavement of what is now considered “white” people through indentured labor or forced labor for rebels who were deported to the colonies. But in the latter case, in large part because of the increased enslavement of Black people along with the growing labor unrest that threatened social stability and elite profits, a shift would take place throughout the 1600s, after which a system of Black racial oppression and a new racial formation of white supremacy would be firmly in place.

Indeed, chattel slavery is central to the story of the invention of the “white race” in what would become the United States and elsewhere. Although it is easy to imagine chattel slavery as being an effect of racism, it is more accurate to say that racism was an effect of chattel slavery. Whiteness and Blackness were invented to produce a dividing line between Europeans and Africans in British America. Rich and poor whites were said to have more in common with each other than with anybody not sharing their outward appearance, while Indigenous populations were placed in a separate category. This racial formation was accomplished in part through the interplay between representations of Black people as non- or subhuman, and through laws that, for instance, enshrined racial slavery and the status of Black people as property in the founding documents of the United States. Meanwhile, whites of all classes were successively granted privileges — chief among them, prior to the U.S. Civil War, were the presumption of liberty, right to immigration and naturalization, and right to vote. In her book “The History of White People,” Historian Nell Irvin Painter notes that “the abolition of economic barriers to voting by white men made the United States, in the then common parlance, ‘a white man’s country,’ a polity defined by race and limited to white men.”

The construction of a racially structured society was further accomplished through legislative and cultural means as well as racialized violence. At a time when abolitionism was gaining a stronger footing in the United States, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 held that Black people — whether free or enslaved — had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect” and codified beyond doubt the racist foundations of the U.S. American polity. The decision would be nullified with the abolition of slavery, but the sentiment remained. Reconstruction failed miserably, as has been noted by writers from W. E. B. Du Bois to Carol Anderson, and anti-Black racism only increased in the following decades, bringing with it a wave of vociferous and violent white supremacy. Other socioracial hierarchies were constructed elsewhere by other colonial European powers and have continued to be constructed into our own time. That doesn’t mean all white people were treated as equals, in the United States or elsewhere; rhetoric and reality often diverge.

Efforts to maintain white supremacist racial formations were increasingly couched in scientific language throughout the 18th century.

Efforts to maintain white supremacist racial formations were increasingly couched in scientific language throughout the 18th century. Through the taxonomic efforts of naturalists like Sweden’s Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), whose classification of living organisms (1735) included a division of humanity into different “varieties” (European, American Indian, Asian, and African), race was factored into humankind’s place(s) in the Great Chain of Being. Writing in the early 1700s, historian Henri de Boulainvilliers (1658–1722) claimed that France’s ruling class was descended from the superior Germanic Franks, linking class to nascent racial thinking. In England, too, myths of superior Germanic blood were foundational to the creation of an “Anglo-Saxon” people, whose imagined racial supremacy formed the basis for a new national identity movement. By the Enlightenment, ideas about “race” had become commonplace and many leading European thinkers of the day were well versed in racializing languages. Although many naturalists like Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707–1788) saw differences in pigmentation, for example, as environmentally based, they often nonetheless ranked the “races,” assuming white Europeans to be superior at all turns (and those “races” living in less propitious environs as “degenerated” in one way or another).

This is not to say that the “science” of race as it emerged in these years was consistent or uniform. In the 1795 third edition of his pamphlet “On the Natural Variety of Mankind,” German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, who introduced the label “Caucasian” to describe white people, “gamely notes the existence of twelve competing schemes of human taxonomy and invites the reader to ‘choose which of them he likes best,’” writes Painter. Blumenbach’s own schema of five “races” gained widespread acceptance, but racist theorists have never managed to agree on a stable number of supposedly immutable races. By Blumenbach’s third edition, skin color played a large role in what was considered the science of race. He included skin color in his taxonomy and ranked white skin the highest, as belonging to the “oldest variety of man,” although skin color was ascribed to climate and experience rather than innate qualities, and “Caucasian” whiteness was extended as far as the Ural Mountains and Ganges. There was also an ongoing struggle in the 19th century between people who advocated a monogenetic understanding of humankind’s origin and those who advocated a polygenetic understanding. Adherents of the former believed that all human races shared the same origin, whether divine or natural, but had since diverged, while the latter instead believed — heretically to some — that different races had different origins.

By the dawn of the 19th century, race was being turned into biology and classified as something ostensibly “natural.” Supposedly innate differences between whites and “inferior” peoples were increasingly used as a justification for the unequal distribution of rights and resources, even as doctrines of “natural rights” were widely touted. While other thinkers were more influential at the time, ethnologist Arthur de Gobineau’s (1816–1882) posthumous influence would be immense. In his 1853–1855 “Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races,” Gobineau claimed among other things that France’s population consisted of three races — Nordics, Alpines, and Mediterraneans — that corresponded to the country’s class structure. The scientification of race and whiteness continued through uses of naturalist Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution (1859), particularly racialized in so-called social Darwinism, which applied ideas of “natural selection” to humans, and argued that racial and class inequalities were rooted in biological differences rather than social inequities. This worldview was used to oppose social policies meant to help the poor, children, or women, among others, further manufacturing and enshrining differences between not only white and nonwhite people but different classes of white people too. Darwinian assertions were also used to legitimize genocide: the “higher” races were naturally bound to overtake the “lower.”

Other schools of racial thought appeared as well: Craniometry, phrenology, and eugenics are examples of supposedly scientific ways of measuring racial characteristics used to motivate policy and cultural shifts that privileged certain whites, and oppressed or marginalized peoples of color and other whites. These means of racialization allowed for new forms of racial projects, which helped establish racial formations wherein race-based legal and economic organization could form the basis for naturalization and exclusion from citizenship, residential segregation, and forced sterilization, among other things.

Such racialization processes and racial projects would find their most rationalized expressions in what historian George M. Fredrickson calls the 20th century’s three “overtly racist regimes”: Nazi Germany (1933–1945), the Jim Crow U.S. South (1870s–1960s), and apartheid South Africa (1948–1994). All three regimes had explicitly racist official ideologies, expressed their ideas of racial difference most harshly in laws forbidding interracial marriage, legally mandated social segregation, excluded designated out-groups from public office or the franchise, and limited out-group access to resources and economic opportunities. While they differed in their specifics, they all promoted racial formations that anchored and upheld white supremacy against groups defined as nonwhite, whether the major differentiation ran primarily along a color line (white to black) or between different phenotypically white groups (“Aryan” to “non-Aryan”/Jewish).

Darwinian assertions were used to legitimize genocide: the “higher” races were naturally bound to overtake the “lower.”

Although opposition had been brewing for decades, particularly in Black critiques of biologistic or “scientific” racism, it was only around the Second World War and after that established racial thinking was thoroughly challenged in white spaces (and then largely with reference to the critiques offered by white critics). Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler had, to use Fredrickson’s phrasing, given racism a “bad name.” The idea that race is a determinative biological fact was reconsidered and labeled a social myth by, for instance, the United Nations. Explicit interpersonal racism largely became unacceptable in white public arenas in the postwar period, while structural racism remained (and remains) largely unconsidered and unaddressed in many of the same spaces. Nevertheless, the explicitly racist legal organization that upheld white supremacy remained in place in the Jim Crow South and South Africa. The forced sterilization of non- or less-than-white “undesirables” (around 63,000 people, starting in 1935) continued in Sweden until 1976 for the “good of the race.” In the United States, following a 1927 Supreme Court decision to uphold Virginia’s Eugenical Sterilization Act, as many as 70,000 forced sterilizations were carried out. The greatest beneficiaries of the move away from biological race theories were in many cases phenotypically white groups that were granted more secure white racialization.

In their landmark book “Racial Formation in the United States,” Michael Omi and Howard Winant write that in our day, race is primarily a political phenomenon. To a great extent, it always was. The meaning of race is often rooted in political contestation between state and civil society, and among different groups in relation to the state; nation-states have been engaged in racial definition for centuries, determining who can be a citizen, who can marry whom, who can reproduce, who can live where, and so on. A given state’s racial classifications shape people’s status, access, rights, and much more. Those racialized as white in different states frequently work, consciously or not, to maintain their privilege against those not so classified, or engage in a delicate dance to give up enough space to allow some into whiteness while keeping others out. This is not surprising. Whiteness may be a fantasy, but for many who profit from it, it is a fantasy worth believing in. Being counted as white continues to materially and decisively impact on who can live in what ways in much of the contemporary West as well as much of the rest of the world, and if they can even attempt a life there to begin with.

Martin Lund is Senior Lecturer, Department of Society, Culture, and Identity at Malmö University. He is the author of several books, including “Whiteness,” from which this article is excerpted.