Toward Rethinking Self-Defense in a Racist Culture

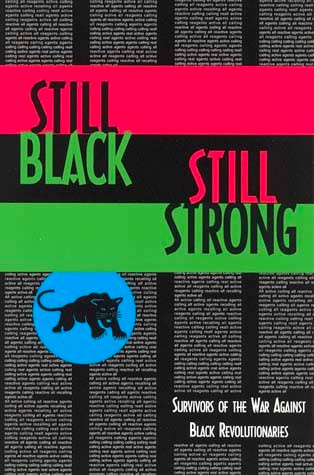

In 1971, Dhoruba Bin Wahad was accused of murdering two officers while still in his teens and imprisoned for 19 years. Bin Wahad always maintained his innocence and won his freedom by forcing the FBI to release thousands of classified documents proving that he had been framed. The justice department eventually rescinded Bin Wahad’s conviction and he was released in 1990. The essay that follows was published three years later in “Still Black, Still Strong: Survivors of the U.S. War Against Black Revolutionaries;” it remains deeply relevant today.

Conventional wisdom holds that peaceful and non-violent change is in the ultimate best interest of a social system. Seldom is the use of force seen as socially productive. By and large this is true. Regardless of the causes, very few civilizations have survived cataclysmic violent internal upheavals, or the long-term decay of their institutions of social control (which amounts to the same thing, for institutional decay results in unreasonable resort to force and repression, thereby causing violent social reaction). If a society thrives through peaceful change, then the exercise of power must be perceived as “just” or at least indicative of a common moral identity. No status-quo power can long maintain itself without some claim to moral integrity unless it does so by use of naked force, and history illustrates that force alone is insufficient to maintain and hold power.

When we rethink the concept of “self-defense” against racist aggression we are also reevaluating the ethical grounds for the use of force in a particular social context. Any concept of “legal” force is determined by the prevailing ideas of those who govern the use of violence.

In U.S. society these prevailing ideas are erected upon the notion of white-skin privilege, that is, of European superiority. This notion holds that a white person’s life is somehow intrinsically worth more than the life of a person of color. This, of course, has played itself out in history. The genocide of Native Americans, the establishment of the African slave trade, and the subsequent era of European colonialism all testify to the fact that white-skin privilege ideologically justified the use of violence in pursuit of European profit and control over people of color. This is the context in which Black people must discuss the idea of self-defense. No rational discussion of self-defense for Black people can proceed without at least this basic understanding.

Perhaps it would be useful to further examine the relationship of force to the American national character, and how this relationship has been institutionalized. Very few people can argue, with any credibility, that the establishment of the United States was a non-violent historical episode. The seizure of the North American landmass from its native population was a decidedly genocidal undertaking. The consistency of this enterprise over such a long period of time — over 250 years — refutes any notion that European racism was merely the aberration of a particular era. The use of African chattel slave labor to establish the foundation for the great North American economic and industrial “miracle” was steeped in ruthless cruelty and maintained by the omnipresent threat of violence.

When we witness the countless incidents of racist police brutality and murder that are an everyday feature of the Black experience in the U.S., it is evident that there is a double standard when it comes to the use of violence: one standard for Europeans and another for people of color.

It is estimated by some historians that over 20 million Native Americans were killed by European settlers of the Western hemisphere between the 15th and 19th centuries, and that over 50 million Africans died in the middle passage between Africa and the Americas in the period between the 16th and 19th centuries. In the early 20th century, the projection of U.S. power into Central America, the Caribbean and elsewhere proceeded in the wake of gunboats or relied upon the bayonets of U.S. Marines. Indeed, the U.S. has invaded Central America over two dozen times in the last century, and has annexed territories it seized from other European colonial powers defeated in ”just wars.”

In the words of a 1960s activist, “violence is as American as apple pie.” Force and violence are part of the American male “folk wisdom” that socializes generations of white males into macho notions of aggression toward people of color. One small example of this is the cliche that the West was “won” by the six-shooter. Indeed, the sanctimonious glorification of equality based upon force could be summed up in a play on the words of the U.S. Declaration of Independence which states that “all men are created equal.” A popular saying on the 19th-century frontier was that “God may have created men, but Sam Colt made ’em equal,” Sam Colt, of course, being the renowned American gun-maker and founder of Colt Firearms Corporation. Flowing out of the notions of white-skin privilege and the white-male “frontier mentality” is the subconscious presumption (now normative for white American cultural ethics) that all Europeans have a moral right, even a responsibility, to use force whenever their position is threatened, and that people of color have no equivalent moral right to defend themselves from European aggression — especially when the aggression is cloaked under the name of “law and order” or U.S. “national interest.”

When we witness the countless incidents of racist police brutality and murder that are an everyday feature of the Black experience in the U.S., or the use of U.S. military force in Nicaragua, Grenada, Panama and the Persian Gulf, it is evident that there is a double standard when it comes to the use of violence: one standard for Europeans and another for people of color. It has been said that “patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” Perhaps it can be said as well that racism is the first refuge of the insecure. Racism, having exercised considerable influence in the development of western nation states, has built into these states this dual standard of humanity, which is so ingrained that it is often taken for granted. As a consequence, “freedom” for the national “racial” minority, as a whole, often requires the radical disruption of the social status quo and a complete reevaluation of the dominant values and norms. It is little wonder therefore that the demand for human rights by the victims of racist subjugation is always perceived by the dominant culture as unreasonable and threatening. Nowhere is this better illustrated than around the issue of force, as it relates to self-defense against racist violence.

In the United States, poor people and especially African Americans are universally encouraged to pursue non-violence in their struggle for human rights. It is argued on the one hand that “violence” per se is unproductive and only begets more violence, and, on the other hand, that “you can’t win any way.” “You” of course being the poor person of a darker hue. Subsidized by “liberal” foundation grants, institutions exist to train the poor in non-violent attitudes and actions. The main stream media, decidedly male and white, while bombarding the populace with esoteric violence in the form of cop shows and Rambo movies, send the subliminal message to the white male population that the use of force and violence by underclass African-American and Third World peoples is by its very nature either criminal or morally suspect. African-American history is rewritten to emphasize the “non-violent” struggle for human and civil rights, while equally heroic but violent examples of struggle are pigeon-holed and dismissed.

Even the history of “non-violent” activism in the African-American struggle for “equality” is presented in a sterile light. The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. is consistently portrayed by the mainstream white media and in American history books as a toothless moral dreamer who essentially endorsed the proposition of the American capitalist state and its support of reactionary movements around the world. Of course nothing is further from the truth. Clearly, “non-violence” as preached by the mainstream media to Black Americans and the poor is never put forward as a tactic, but as a goal in itself.

While the disenfranchised Black community is fed the psychological pablum of non-violence, the enfranchised majority white community trains its children in the use of force in its war colleges and police paramilitary institutions. Moreover, Eurocentric American nationalism provides the mass culture with a moral and ethical framework in which to act out the violent impulses of their institutional training. The tradition of “conservatism” and the “right” are fundamental standards by which all other perceptions and views are measured. Thus an unfair imbalance is achieved between the benefactors of a racist society and its underclass. Indeed, the so-called “liberal” American tradition operates within this race- and class-bound imbalance, which is one reason why the so-called “two-party” (Democrat-Republican) body politic and the principle of separate branches of government are bankrupt, and never prevented U.S. intervention in the Third World, e.g., Korea, the Congo, Vietnam, Grenada, Angola, the Middle East, Libya and Central America, and it never secured for African-Americans equal and fair treatment under existent law.

While the disenfranchised Black community is fed the psychological pablum of non-violence, the enfranchised majority white community trains its children in the use of force in its war colleges and police paramilitary institutions.

The obvious consequence of a dual standard of human expectation is a unique system of democratic fascism and a permanent condition of police or military repression aimed at the underclass and social dissidents. Limited political “democracy” is permitted while corporate control of the economy dictates the real content and direction of the state. In this context the specter of racist subjugation resolves itself in an ongoing and continuous cycle of police repression, underclass crime and social deprivation-in other words a permanent state of crisis.

The highest expression of this system of democratic fascism appears to be the “National Security State,” or NSS. This Orwellian corporate government structure has developed both as a corporate political manager of, and a reaction to, the condition of permanent domestic social crisis and an insurgent post-colonial Third World. The American NSS, as an institution, sponsors and sanctions racist violence of “law enforcement” at home and euphemistic “low-intensity conflict” in the Third World. In terms of its breadth of organization and its management of violence as an instrument of policy, the NSS is the ultimate purveyor of force on the face of the earth.

The bureaucracy and technocrats of the NSS serve the transnational interests of corporate America. It derives its strength and power from control of technology, a huge military-police apparatus, and its capacity to control the primary sources of information. Because the NSS sees itself as preserving “the American way of life,”. i.e. status quo power, it views its own citizens as subversive to “national security” whenever they disagree with the police or the interests of the NSS. Consequently “law enforcement” takes on a decidedly political function. Behind criminal law enforcement lurk the political police whose job it is to contain the unruly, quiet the outspoken, and destroy the dreamers of a new order.

Behind criminal law enforcement lurk the political police whose job it is to contain the unruly, quiet the outspoken, and destroy the dreamers of a new order.

Effective mass organization of people against racist/class inequality, against high minority unemployment, against socio-economic dislocation (homelessness), or for the redistribution of wealth, reorganization of national priorities, and social control of technology, is always seen by the NSS as disruptive of the status quo. For this basic reason, essentially moral and economic issues such as street crime, drug abuse, criminal justice, or the African-American “underclass” are political campaign issues gratuitously used to manufacture an ill informed public consensus which endorses “democratic” repression of dissent and of the disenfranchised, as the Willie Horton issue was used by the racist right during the 1988 presidential campaign. An accurate assessment of the use of violence against minorities in a racist culture would be very difficult if African-Americans did not take a serious look at the nature of the National Security State.

Covert Action Information Bulletin (CAIB), a Washington, D.C. based non-profit civilian watchdog organization, recently reported the existence of the little-known “State Defense Forces” (SDFs) being created throughout America. According to CAIB, these “State Defense Forces” (a generic term) have been organized in approximately 24 states as auxiliaries to the already legally constituted state National Guard. It is presumed that a domestic SDF will be needed to control dissent and civil unrest in the event of a national emergency arising out of an unpopular U.S. military invasion abroad in which the National Guard is federalized and sent overseas. Recruits for the SDFs are unpaid civilians, and though it appears that anyone can join the SDF, its ranks are at present filled by zealots of the political right.

This is significant, especially for African-Americans who are considered by the NSS to be an acute threat to America’s “domestic security” by virtue of the justice of their grievances. It should come as little surprise to know that the SDF cadres are being trained in urban riot and crowd control, and in the use of weapons such as shotguns, M-16s, M-60s and 45-caliber pistols, as well as in various police techniques of anti-insurgency. While African-Americans are being taught, trained and indoctrinated into a non-violent frame of mind, the white American National Security State is teaching, training and indoctrinating its adherents to employ lethal force in suppression of dissent and protest. This is not a coincidence. The violent mentality of the racist status quo and the white fear of Black America are almost symbiotic in nature. This seeming symbiosis has as its objective the denigration of the political option of self-defense for people of color, and the criminalization of the advocacy of such options. Thus, people of color are encouraged to rely on the very system of violence that subjugates them.

The violent mentality of the racist status quo and the white fear of Black America are almost symbiotic in nature.

In January of 1989, Don Jackson, a Black police officer on leave from the Hawthorne, California police department drove through predominantly white Long Beach, California on a personal fact-finding mission. He was investigating reports of racist police harassment. Mr. Jackson was shadowed during his drive by an unmarked KNBC-TV van. What happened to Mr. Jackson was nationally televised in graphic detail: he was stopped arbitrarily by policemen from Long Beach, one of whom slammed his head through a plate-glass window to impress upon him exactly who was boss. Mr. Jackson wrote in a January 23rd New York Times op-ed article, “Police Embody Racism to My People,” that police brutality inflicted on Black people has a greater historical function than mere gratuitous violence:

The black American finds that the most prominent reminder of his second-class citizenship is the police. In the history of this country, police powers were collectively shared among whites regarding black people. A slave wandering off the plantation could be stopped and detained by any white person who saw fit to question his purpose for being away from home… A variety of stringent laws were enacted and enforced to stamp the imprint of inequality on the black American. It has long been the role of the police to see that the plantation mentality is passed from one generation of blacks to another. No one has enforced these rules with more zeal than the police. (emphasis added)

The irony of Mr. Jackson’s assessment is that the “collectively shared” police powers of whites has given way to a collectively shared perception of Black people as potential criminals and terrorists. Indeed, even Mr. Jackson’s effort to expose the truth fell victim to the need for white society to obscure it. The dramatic racist police mistreatment of Mr. Jackson was juxtaposed on national news broadcasts next to Black people “looting” white and immigrant Hispanic-owned stores in Miami. The white media, as if by reflex, played to the dual realities of a racist culture. Surely white America got the message that the police have their hands full dealing with potentially volatile Blacks, and that if they are somewhat aggressive, who can really blame them? At the same time, Blacks were made to feel as if their truth was being told. The duality of historical experiences — one Black, one white — whatever the facts, makes “democratic” consensus without equal power impossible.

Equal power? What does this mean for African Americans? Perhaps we would do well to reevaluate our idea of what equality means, for if we are of the notion that individual freedom in a racist culture can be acquired at the expense of the collective freedom of the victims of that culture, then we have accepted the amoral concept of “equal opportunity exploitation,” the very same concept that enslaved our ancestors and which divides the world today into two antagonistic divisions of “haves” and “have nots,” exploited and exploiter. Malcolm X once said, “history is the best subject to reward all research.” There is no way we can judge the relationship between African-Americans and European-Americans under imagined conditions of equal power, that is, absent our history of subjugation, absent the consequences of chattel enslavement driven by profit incentive, or regardless of the elaborate edifice of legal and social discrimination erected to maintain African-Americans in a purely “minority” status in which their interests are subsumed by the interest of the dominant caste and class.

The common humanity of both African-Americans and whites has had to endure and suffer the predatory appetite of a system devised to enrich the few at the expense of the many.

The common humanity of both African-Americans and whites has had to endure and suffer the predatory appetite of a system devised to enrich the few at the expense of the many. Whatever episodic sparks of humanity that the races may have exhibited toward each other surely occurred despite the European nation-state system-not because of it. The struggle for Black empowerment can ill afford to ignore history. There is no power without the capacity for independent self-defense.

Whenever the question of Black self-defense arises, it inevitably stumbles over the issues of “legality” and “appropriateness of violence” (which all too often amount to the same thing, that is, violence is always considered appropriate if — and only if — it is “legal”). This is because self-defense against racist attacks is generally viewed in a very narrow fashion which is unjustified by our experience as a people. To combat this, in the first place, the idea of the use of force to defend oneself has to be stripped of racist duality. Secondly, we have to understand the function of force as the European power elite perceive it, and third, we must evaluate the utility of a newly derived definition of self-defense in assuring collective survival.

Should we examine Mr. Jackson’s historical assessment of police violence we would see that it is the same as the organization of racist terrorism. Violence was historically used in conjunction with other psychological factors to dehumanize the African slaves and secure their system of servitude. For the men who controlled this system, slave control was not only an economic consideration but a matter of physical self-defense as well. The fears of Native Americans and of African slave revolt were two permanent features of early European-American colonial life. In 1710, the governor of Virginia, Alexander Spotswood, advised the Virginia Assembly in these words:

Freedom wears a cap which can, without a tongue, call together all those who long to shake off the fetters of slavery, and as such an insurrection would surely be attended with most dreadful consequences, so I think we cannot be too early in providing against it, both by putting ourselves in a better posture of defense and making a law to prevent the consultations of Negroes.

Apparently the honorable governor’s advice did not fall on deaf ears because the Virginia slave code mandated that should a slave run away and not immediately return, “anyone whosoever may kill or destroy such slaves by such means as he shall think fit.” In addition the courts had authority to order dismemberment or any other measure “as they in their discretion shall think fit, for the reclaiming of any such incorrigible slave, and terrifying others from like practices.”

Other examples abound of the terroristic use of violence codified into law with the express purpose of maintaining our ancestors in a position of abject fear and servitude. If times have changed, the residual and accumulative benefits of white-skin privilege still ensure the legal codification of violence in maintenance of the status quo. It is this status quo, with all the moral righteousness of the founding fathers behind it, that now preaches against the evils of terrorism. Former President Ronald Reagan admitted to a profound historical analogy when he equated the terrorist and murderous CIA-backed Nicaraguan “Contras” to the “moral equivalent of America’s founding fathers.” To borrow a phrase from the distinguished Governor Spotswood of Virginia, African-Americans would do well by putting themselves in “a better posture of defense.”

The purpose in drawing attention to early American history is not to revel in moral self-righteousness or engage in useless judgment of another period when behavior and attitudes were determined by different standards than today. It should not be too difficult to see that the “founding fathers” of America were men of property driven by the contradictions of European culture, a culture based on agriculture, with feudal hierarchies of the nobility (lords), vassals and peasants, which evolved from the slave societies of Greece and Rome. History is clear: erected upon the European conquest of North America, upon the genocide of the Indians and the racist brutality of slavery, Europeans stratified a civilization based on private property. The European need for land and space, combined with the dubious ethics of mercantile capitalism, made racism and genocide integral to the society and system we know today. The rhapsody of the American dream sold to countless immigrants is only a part of the true story. We must understand the truth of our historical experience so that we are clear in our thinking and fully appreciate what America is capable of.

Racism has been an important tool in dividing the poor and working peoples of America. It has prevented white laborers, the middle class, and various Third World immigrant communities from uniting against an exploitative and relatively small white male elite.

Racism has been an important tool in dividing the poor and working peoples of America. It has prevented white laborers, the middle class, and various Third World immigrant communities from uniting against an exploitative and relatively small white male elite. Despite this objective “function” of racism it would be inappropriate for the African-American to ignore the very real physical threat racism represents to our empowerment. In the struggle for power, often perception is more important than reality.

The common Eurocentric perception of African-Americans is that they lack certainty of principle and a willingness to defend themselves. Our self-destructive treatment of each other, that is, our obsessive imitation of the most shallow white American values, our disregard for Black youth, “Black on Black crime” and the entire range of psychotic self-hatred we act out every day in our social relations reinforce white Americans with negative perceptions of Black people. Many of the problems that now confront African-Americans begin at home, in our community. Until we establish independent mechanisms of community supervision that provide moral, ethical, political and social direction, African-Americans will continue to be the doormat of U.S. society. Depending on outside forces to regulate and govern the African-American community is a prescription for disaster. A community without internal authority and control is no community at all.

Weakness tempts power to practice brutality and oppression. The seeming increase of so-called “racially motivated attacks” is in large part the consequence of the apparent inability or unwillingness of Black America to defend itself. While the term “racially motivated attack” is a media buzz word intended to individualize systemic racist subjugation, we need not fall victim to this deception. There is nothing exceptional or individual about racist attack in a racist society. Media buzzwords notwithstanding, our response to racist attack must be collective, uncompromising and most of all organized! We should respond in a political manner to all racist attack, as well as to conditions that invite attacks. Both legal racist violence (police, state and institutional brutality) and extra-legal racist violence (racist gang violence, individual discriminatory treatment) serve the same function: the subjugation of the targeted racial national minority. Black people must break with the mental baggage of slavery and shed the knee-jerk “non-threatening negro” posture white folks love so well. Our concept of force, its political utility, is obsolete. Force and violence must be seen for what they are and placed in a relevant political context: instruments of political power, instruments of control.

Depending on outside forces to regulate and govern the African-American community is a prescription for disaster. A community without internal authority and control is no community at all.

The violence of racist oppression, when internalized by the African-American community, results in reactionary violence or negative violence, and it must be repressed by the African community if self-defense is to advance beyond vigilantism. Vigilantism is not the political organization of force-it is the social organization of civilian frustration. It can be co-opted by the status quo, misdirected by opportunists, and will eventually fizzle out. The political organization of force by the Black community implies its connection to the struggle for power and control over the entire quality of life available to Black people. Unlike reactionary apolitical violence, or vigilante force, the concept of Black self-defense, e.g. the political organization of force, is proactive force. Self-defense in this context is as broad as the requirements of and the struggle for empowerment. Legality and illegality are relative to the struggle for empowerment — not sacrosanct in and of themselves. White folks taught us the efficacy of this approach to this use of force.

By way of example, the tactic of economic boycott can be seen as an economic form of self-defense against economic exploitation, injustice or discrimination — especially when it upsets the colonial relationship between the African American community and the status quo power. In this sense it is proactive and not reactive. Taking control of social institutions or educational systems that affect the quality of African-American life by establishment political means, i.e. electoral politics, and the creation of grassroots alternative institutions which provide services to the Black community are forms of proactive self-defense, for a primary objective of self-defense is deterrence, and a limited political power is better than no power at all. But it is not always enough to deter racist attacks.

Black Americans can never relinquish the right to exert a political consequence on those institutions and individuals who abuse us. Questions of “legality” and “illegality” are relative — the appropriateness is both tactical and ethical. Insofar as Black America is unable to punish racist brutality and exert a political consequence for racist attack we are weak, vulnerable and unequal. It is a moral imperative to organize Black people to defend themselves. We must get away from the plantation mentality and the cowardly notion that organizing force in defense of Black people and in pursuit of our political objectives, when necessary, is somehow amoral and therefore rightly illegal. All people have the right to defend themselves. Moreover, all that is legal is not morally just.

The proper criterion for distinguishing between “right” and “wrong” is not mysterious. It is embodied in the principles that advance the cause of the oppressed and exploited over the cause of those who live by oppression and exploitation. Even though the oppressed and exploited may not always be “correct,” their cause is just and right. Nor should we foolishly imagine that, by following the guidance and leadership of those who uphold the cause of the oppressed, we are somehow conferring favors on such leadership. For leadership is a burden — surely the more one knows, the more one is responsible for. This is why current Black leaders act like they don’t know what’s happening in times of crisis, because white folks will hold them responsible for the consciousness of the masses. Our leaders must be responsible to us — not to the status quo, which demands that our people remain in check.

Our leaders must be responsible to us — not to the status quo, which demands that our people remain in check.

Humankind has a weakness for falsehood, vanity and crookedness, not because we are inured to truth and selfless devotion to community, but because it is much easier to pursue falsehood and vanity than to seek truth and social responsibility. So it is, that the delusions of the material world gratify us and yet leave an aching emptiness in our soul. Perhaps this weakness is why African-Americans, in the tradition of Western materialism, would much rather follow a fool dressed in a silk suit than a wise righteous person draped in rags. We fold our hearts like a handkerchief, tucking it away in our back pocket, sitting on it as if embarrassed that we possess a heart at all. Surely the corruption of a person’s heart is a great tragedy — for the malaise of the human spirit is reflected in the social condition of a people. Their need arises from the drifting and unfocused hunger of Black America for a class of men, women and youth committed to upholding the social, moral, ethical and spiritual integrity of our community — no matter how great the sacrifice. We need to care more about ourselves than about what white folks think about us, and in so doing realize that “history does not respond to those who lack the basic instruments of bringing about historical change.” This means we must acquire independent power. The rhetoric of “liberalism,” “left” dogma, or “right” integrationist accommodation are passe, obsolete. They are without moral or ethical integrity and of limited utility to Black America in crisis. The crisis of Black America is not only material (i.e. economic), or political, or even social. It is at its root a malaise of the heart — of the spirit. The reality of the nation-state in which we live is in transition. Our struggle for liberation as a people must reflect this and invigorate us with a new sense of direction and purpose.

We need to care more about ourselves than about what white folks think about us, and in so doing realize that “history does not respond to those who lack the basic instruments of bringing about historical change.”

The world is changing. It is in a transition from a world order dominated by European economic hegemony born out of racist colonialism to one in which that system of domination is under increasing strain to accommodate the interests of the disenfranchised. Increasing awareness of the need for a world order and redistribution of wealth unencumbered by selfish class-based nationalism is rising in the world. Technology has placed humankind at the crossroads of history. What will be Black America’s role in the historic struggles that lie ahead? Black leaders who do not frame the struggle in this context are not Black leaders at all.

While we must prepare ourselves collectively to wage many struggles at once, we must do so with a common sense of mission and purpose. Without this sense of mission and purpose we will succumb to the spiritual and material degradation of a racist culture. The times in which we live portend both hope and doom.

During the long centuries of the slave trade, Africans had a sense of mission, of common purpose to survive and defeat the brutal system of dehumanization and “break de’ chains.” In post-Reconstruction America, when the national agenda was set for the remainder of the century by putting “Negroes” back in their place as neo-serfs (sharecroppers) and servants, Black people had a sense of collective mission. When white labor was bludgeoned into submission by the robber barons of commerce, and the political elites of both North and South consolidated the economic wealth of America into the greatest material growth in human history, Black people had a sense of mission, purpose and common direction which culminated in the upheavals of the early- and mid-20th century for civil and human rights. We must rekindle this flame and sense of purpose, but on a much higher level. We know what white America is capable of when it comes to people of color. We understand the limitations and imperatives of history, and a racist culture. The question therefore is what do we intend to do about it.

Dhoruba al-Mujahid bin Wahad is an American writer and activist, who is a former prisoner, Black Panther Party leader, and co-founder of the Black Liberation Army. This essay is excerpted from “Still Black, Still Proud.”