The Identity Crisis of America’s Largest Anti-Hunger Program

When Walter Willett speaks, people listen. Among the world’s most cited nutrition researchers, Willett, who chaired the Department of Nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health for 25 years, has been an outspoken advocate for evidence-based policies that run counter to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s cozy relationship with the food industry for over four decades. He campaigned to discredit the USDA’s food guide pyramid, a deeply flawed and now-defunct infographic that was shaped by agribusiness lobbyists; he has steadfastly criticized the agency — and the dairy industry — for unscientifically pushing milk as a superfood; and he fought tirelessly to get trans fats out of our food supply (they were eventually banned in 2015).

Willett’s record isn’t entirely unblemished, however. He’s been criticized by some for oversimplifying science for the sake of delivering a clear public health message and for allowing his ideological views to influence his research. Others, meanwhile, have lambasted the field of nutrition science itself, citing, among other challenges, the messy nature of observational studies.

So when Willett and a team of nutrition scientists at the Harvard School of Public Health began to produce a prodigious array of research papers that were critical of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — also known as food stamps — they quickly caught the attention of Jim Weill, the longtime president of the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC). The leading lobbying force for federal food assistance programs, FRAC has spent half a century fighting to protect, grow, and improve the food stamp program through multiple hostile administrations and congresses. To Weill, Willett and his colleagues’ research laid bare SNAP’s weak flank and left it open to partisan spin.

Centering in large measure on the potential exclusion of unhealthy foods, such as soda, from the list of permitted products within SNAP, Harvard’s findings suggested that the USDA’s cornerstone program could play a much greater role in combatting an ever-widening obesity epidemic that especially affects the low-income persons eligible for food stamps. The research couldn’t have come at a worse time. Republicans were proposing to slash billions from SNAP in the Farm Bill. And Representative Paul Ryan’s budget plan sought to devolve SNAP to the states, a move that likely would have gutted the program’s effectiveness. As SNAP defenders saw it, the barbarians were storming the gates, with Harvard’s research potentially supplying ammunition to the enemy.

In 2012, as this conflict was coming to a boil, Weill requested a meeting with Willett and his colleagues. Joined by a FRAC senior nutrition policy and research analyst, he traveled to Boston later that year. Harvard’s nutritionists saw this meeting as a good-faith effort by both sides to find common ground that would importantly preserve the program and secondly improve it. They staunchly opposed cutting benefits, since they were all in agreement that food insecurity is a massive problem in the United States, with serious health implications.

As SNAP defenders saw it, the barbarians were storming the gates, with Harvard’s research potentially supplying ammunition to the enemy.

According to one of the participants, the message Weill delivered was clear: While he believed it to be well-intentioned, Harvard’s research undermined the nation’s social safety net and had to be put on hold until a more politically opportune moment arrived.

When pressed to explain substantial cash donations that FRAC accepted from the food and beverage industry — donations that could have created a conflict of interest — the mood became tense. Maintaining that the funding did not affect their position on the continued inclusion of soda in the food stamp program, but likely feeling his organization’s integrity challenged, Weill called an abrupt halt to the meeting.

While this encounter is almost a decade old, it perfectly illustrates the longstanding tensions between the public health and the anti-hunger communities and raises fundamental questions about the very nature and purpose of the SNAP program: Is SNAP essentially an anti-poverty program, whose benefits are primarily a form of income redistribution? Or is it, as its name states, a program that seeks to improve the nutritional status of its participants? Should health promotion be considered a primary goal of the program? Moreover, the conflict touches upon foundational issues regarding the government’s regulation of the food industry, to questions about a person’s freedom of choice and personal dignity in the context of a market economy, and the ethical responsibility of nonprofit organizations to their constituents.

The debates over the purpose and functioning of SNAP have been shaped by the changing demands on the program, and by the dynamic environment in which it has operated since 1933. The Roosevelt administration established the food stamp program during the Great Depression to augment farmers’ income by creating an additional market for their products. The program languished in the 1950s, until the Kennedy administration reinstituted it in 1961. By then, its importance in bolstering the farm economy was supplanted by an increased emphasis on its role in reducing hunger, in part due to growing pressure from the civil rights movement. Made permanent in 1964 and further modified in 1977, the food stamp program’s raison d’être soon became its ability to improve the nutritional status of the food insecure.

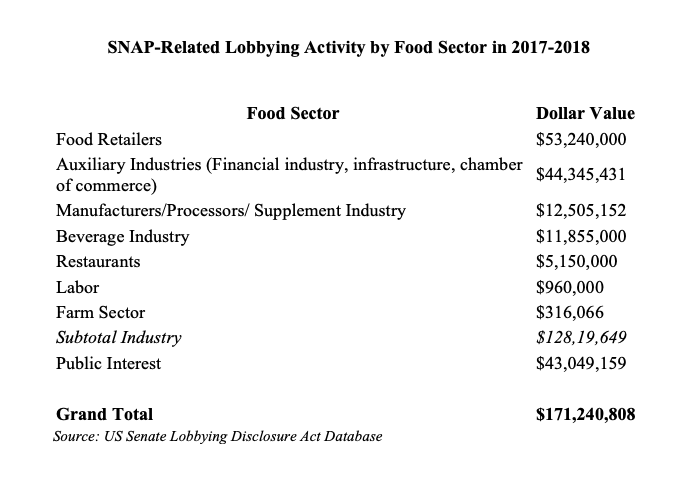

Throughout the 1960s and until recent times, food stamps have enjoyed strong support from the agriculture industry. As retailers and processors displaced farmers in capturing an ever-greater share of the food dollar, their importance as stakeholders for the program grew. In the 2018 Farm Bill, banks, refrigeration equipment manufacturers and even the U.S. Chamber of Commerce join food retailers, beverage companies, and manufacturers as key stakeholders in the SNAP program. These players have evolved into much more important participants in the program than farm groups, as evidenced by the amount of money they spend on lobbying.

The support of the agriculture and food industries has fundamentally shaped the evolution of the food stamp program. The United States remains the only major nation with a program that supports the poor not through cash, but through transfers linked to its own agri-food industry. Because food stamps have been essentially a form of aid tied to industry, the program’s structure has been downstream to the nature of the marketplace.

Congress has adopted a laissez-faire approach to SNAP recipients’ food choices. With the exception of minimal restrictions around hot foods, the government has allowed the purchases of the food stamp program to shift with broader societal trends. For example, if we as a society consume more processed foods and drink more sugary beverages than we did 20 years ago, then changes in the purchases made with SNAP benefits have simply reflected those trends.

Food stamps never evolved into a cash transfer program in part because the economic benefits provided to the agriculture and food industries have helped the program gain bipartisan support. While many anti-hunger advocates see such a cash transfer as more dignifying than food stamps, they have strenuously opposed cashing out the program in full knowledge that cash distributions would be easier for Congress to slash in the future than food vouchers. Decoupling food stamps from its history as a food program would not only remove the impetus of the food industry to lobby for it, but also taint the program as a welfare initiative. For many anti-hunger advocates, food stamps are an income transfer program cloaked in the politically safer nutrition framework.

For many anti-hunger advocates, food stamps are an income transfer program cloaked in the politically safer nutrition framework.

The meaning of food stamps as a nutrition program has shifted as the public health context evolved. Food stamps and other federal food programs had largely eliminated the malnutrition that shocked the nation when highlighted in the 1960s. Severe hunger and the illnesses that accompanied it eventually gave way to the rise of chronic diseases, such as heart disease, obesity, and diabetes. These diseases were caused by malnutrition of a different nature, more prevalent among the impoverished, but still a result of poor diet. Infectious diseases and diseases of underconsumption gave way to chronic illnesses and ailments related to overconsumption.

This “nutrition transition” opened the door for new constituencies to weigh in on the food stamp program. In particular, the public health nutrition field targeted SNAP as an important potential tool for diminishing the excess rates of diet-related diseases among the poor. They challenged the anti-hunger community to reprioritize food quality over quantity, and nutrient density over energy density. They identified the food system’s core competence of producing calories efficiently and cheaply as no longer a virtue, and sought to decouple the SNAP program (as well as other federal food programs) from this cheap food policy. In essence, they sought to redefine what it meant for SNAP to be a nutrition program, beyond its traditional accomplishments in reducing hunger, to one of prevention of chronic diseases. Congress embedded a symbolic yet powerful nod to the importance of nutrition to the food stamp program when it renamed it as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the 2008 Farm Bill (before this it was called the Food Stamp Program).

By the 2012–2014 Farm Bill cycle, however, SNAP’s political cover was wearing off, and the very heart of its protective shield, its nutritional effectiveness, came under attack. Arguably, the nutrition community’s critiques about the ineffectiveness of SNAP to address the burgeoning obesity and diabetes epidemics provided ammunition to the program’s opponents. SNAP recipients’ food choices became a rallying point around which Tea Party acolytes could converge. Conservative politicians and large sections of the public expressed moral outrage at the dietary preferences of SNAP recipients, either because they perceived them to be eating luxury foods such as crab legs, or junk food such as soda and chips.

The battle over the nutritional content of foods eligible for purchase in the food stamp program can be seen throughout its history. In 1941, the USDA temporarily removed soft drinks from the list of eligible foods. In 1964, Senator Paul Douglas (D-IL) sought to remove “frozen luxury foods” and soft drinks from the program but was rebuffed in part because research showed that participants were already consuming a healthy diet. In 1975, writing for the right-wing American Enterprise Institute, Kenneth Clarkson criticized the nutritional value of the food stamp program for the “little positive contribution to diet improvement and apparently worsen[ing of] the diet of some food stamp recipients.”

27 years after Clarkson’s report, another American Enterprise Institute–associated writer, Douglas Besharov, disparaged federal nutrition programs. He claimed that these programs made little progress in addressing the rapidly expanding obesity epidemic, blaming anti-hunger groups for maintaining the status quo. This attack put anti-hunger groups on the defensive, breaking up what should have been natural alliances between public health and hunger groups.

Anti-hunger leaders fear that opening up SNAP would give their right-wing opponents an entry point to cut the program and devastate the food security of tens of millions dependent on it.

Leading anti-hunger groups were circling the wagons long before Besharov’s 2002 op-ed. Anti-hunger leaders appeared to have made a strategic decision that, in the words of one long-time advocate, “going into ostrich mode” was a safer political bet than engaging in a dialogue about improving the nutritional effectiveness of the food stamp program. In this calculus, advocates compared opening up SNAP to a Pandora’s box that would give their right-wing opponents an entry point to cut the program and devastate the food security of tens of millions dependent on it. They essentially calculated the public health and food system advocates as less politically powerful than the Right, and able to be fended off for the time being. They made a devil’s bargain, one could say, protecting the food security of tens of millions of poor persons in exchange for dropping the ball on addressing the obesity and diabetes epidemics among this same population. This choice was a no-win situation, a short-term pyrrhic victory at the long-term price of the health of their constituents.

Around the same time as FRAC was meeting with Harvard nutritionists, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, in conjunction with the State of New York, requested a USDA waiver of SNAP program rules to ban soda for two years in order to assess the impact on SNAP recipients’ health. The waiver request drew sharp lines between opponents and proponents of the ban.

Ten months later, the USDA denied the waiver request. The timing of the request presented challenges, as it arrived amid a growing rhetoric demonizing poor people as incapable of making good food choices. USDA deputy secretary Kathleen Merrigan and secretary Tom Vilsack believed that granting the waiver might lend credence to this vilification, damaging not only the dignity of the poor, but also the integrity of the SNAP program.

The Right had indeed caught wind of this issue and appropriated it. In at least 25 states, legislators, usually Republicans, championed SNAP restrictions. From their perspective, food stamp recipients could only make bad choices, of either junk food or luxury items, and needed to be led down the straight and narrow nutritional path.

SNAP reformers faced yet another challenge in addition to the USDA’s reluctance to issue a waiver and the might of the beverage and anti-hunger lobbying forces. There is no public data on how SNAP benefits are used. Without this information, the ability to assess which companies have profited from SNAP, as well as to determine what SNAP recipients purchase, is limited.

As for retailer information, the USDA collects but has refused to distribute specific details in order to protect the business interests of its grocer partners; in the highly competitive grocery business, for instance, retailers claim that the release of this information would put them at a disadvantage with their competitors. The Argus Leader, a South Dakota newspaper, sued the USDA to gain the release of this information, winning an initial decision by the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. In June 2019, the Supreme Court reversed lower court decisions, ruling six to three in favor of the retail industry.

In terms of the foods purchased by SNAP participants, such as sugar-sweetened beverages, the USDA does not officially collect nor distribute this information. It did commission a study (released in November 2016) that examined SNAP purchase data from a single supermarket chain in 2011. The report found that 20 percent of SNAP purchases consisted of sugar-sweetened beverages, or SSBs, candy, sugar, and salty snacks. SSBs made up nearly 10 percent of all SNAP sales (which if extrapolated to all SNAP sales would total $6.6 billion in 2011), as compared to 7.1 percent for non-SNAP household expenditures.

For the most part, anti-hunger forces shrug off the need to increase the transparency of the SNAP program. Immersed in trench warfare with the Right, anti-hunger leaders sense that the release of more information could only damage their position. As with the case of Harvard’s research, they fear that it could arm the program’s enemies.

“We don’t ask how people spend their unemployment benefits. Why should food stamps be any different?”

To some anti-hunger advocates, drawing the line on which information should be made available isn’t so straightforward. One senior D.C.-based anti-hunger advocate who spoke with me off the record quipped: “We don’t ask how people spend their unemployment benefits. Why should food stamps be any different?” Viewing SNAP solely as an income assistance program, his comments resonate. He insinuates that as a society we demand a greater level of scrutiny on programs that benefit the poor than we do on middle class-oriented programs.

The theme of holding the poor to a higher standard comes up frequently in conversations with anti-hunger advocates. They feel that, all too often, American society treats the poor paternalistically, because we perceive them as lazy, immoral, or just incapable of making good decisions on their own. This cultural bias carries over to the nutrition field. In supermarkets across the country, the grocery carts of the poor are scrutinized for being too junky or too extravagant. Yet the anti-hunger argument against SSB exclusions goes beyond fighting against this belittling of the poor’s decision-making ability to include more practical and theoretical arguments.

First, anti-hunger proponents believe that advocates for exclusions are barking up the wrong tree. They see SNAP’s nutrition purpose as secondary, at best, to its anti-hunger function. Others deny SNAP as a nutrition program at all. Ed Cooney, the former executive director of the Congressional Hunger Center, asserts, “There is no evidence of SNAP as a nutrition program. It was Joe Baca’s idea (Baca was the chair of the Nutrition Subcommittee in the House Agriculture Committee during the 2008 Farm Bill) to change the name of the program. He didn’t change the program’s mission.” Keith Stern, a former staffer to Representative Jim McGovern (D-MA), a leading voice for anti-hunger programs, agrees: “SNAP is not a nutrition program. It isn’t based on nutrition and doesn’t help people eat healthfully. Its benefits are inadequate, something that (at best) restricts the ability to purchase healthy food and (at worst) promotes the purchase of unhealthy, low nutrient food.”

A Harvard study found that stores in neighborhoods with high levels of SNAP participation increase their marketing of sugar-sweetened beverages by 435 percent during periods in which SNAP benefits are issued.

Second, they believe that a more empowering and effective approach would be to increase benefits, contending that when recipients have more income, they will purchase foods with a better nutritional profile. Anti-hunger groups also contend that SNAP recipients eat no better or worse than other low-income Americans, and SNAP itself does not cause obesity. They hold that the nation’s obesity epidemic must be dealt with systematically as it is the entire food system that ensnares SNAP recipients — and the general public — into poor food choices.

In short, the advocates assert that restrictions will simply not work. From their perspective, with tens of thousands of products on the shelves of 200,000 SNAP-authorized retailers, making science-based decisions on which products would be excluded and then communicating those decisions would be enormously problematic. FRAC reports potential changes would put an increased burden on retailers, many of whom already struggle with existing rules. As a result, many retailers might drop out of the program, further reducing food access for the needy.

Anti-hunger advocates also remain deeply concerned that further food restrictions might result in individuals dropping out of the SNAP program, worsening their food security. Any practice that would identify individuals as SNAP recipients, they say, such as forcing them to separate eligible and ineligible purchases at the checkout counter, would increase the stigma associated with participating in the program.

Underlying these rationales for supporting the status quo of the SNAP program is an unspoken but highly strategic motivation: that excluding SSBs and possibly other junk foods would reduce industry lobbying for the program. FRAC has deliberately built as big and broad a tent as possible for SNAP to maximize its legislative chances. They have made a strategic trade, gaining the support of industry for the program in exchange for allowing them to profit handsomely from the SNAP program. This implicit deal is grounded in the assumption that a SNAP “with warts” does more good for the poor than a smaller health-oriented program or no program at all.

Anti-hunger and public health groups relate to the soda and food industry in starkly different ways. Ed Cooney summarizes this difference: “They [the public health groups] think of industry as predators. We prefer to think of them as partners.” To the public health community, “Big Food” fattens the American population, and especially the poor, through a combination of targeted advertising and manipulation of processed foods to appeal to our biological cravings for salt, sugar, and fat. A Harvard study, for instance, found that stores in neighborhoods with high levels of SNAP participation increase their marketing of sugar-sweetened beverages by 435 percent during periods in which SNAP benefits are issued.

Hank Herrera, a longtime community food security advocate, summarizes this perspective: “SNAP uses poor people as a pass-through intermediary to subsidize the food manufacturers. And in the process, poor people suffer and die from the toxic foods the manufacturers produce.”

To many anti-hunger groups, especially the main national lobbying entities such as FRAC and Feeding America, the food and beverage industries are their friends. Industry buys tables at their galas, writes them six- and seven-figure checks from their foundations, but most importantly, according to anti-hunger leaders, plays a pivotal role in the passage of the SNAP program. “At the Congressional Hunger Center, we do not accept funds that have any restrictions on them. Critics have indicated that this is an unholy alliance,” Cooney told Slate. “I have no objection to that term. Those companies have access to members of Congress that we don’t have access to, people in the Republican leadership. We find this advantageous.”

Anti-hunger groups have actively courted industry groups to protect SNAP from restrictions. Ellen Vollinger, a FRAC staff director dealing with food stamps and legal issues, led the creation of the Coalition to Preserve Food Choice in SNAP, whose members include numerous anti-hunger and farm groups as well as the main trade associations for the soda, candy, baking, snack food, dairy, supermarket, and high-fructose corn syrup industries. Together, anti-hunger and industry groups lobby on state and federal legislation related to protecting “freedom of choice” within the SNAP program.

The fact remains that even under the Trump Administration, the USDA has not issued a waiver to any state wishing to exclude certain foods from the SNAP program, with Maine being the latest high profile case. To date, the department under the Trump administration has sided with the food and beverage industry. In an administration that is both avowedly pro-business and anti-poor, this issue has revealed where the USDA stands in the conflict between corporate profits and the war against the poor.

The fact that no locale has been able to implement such restrictions indicates that the anti-hunger argument is prevailing at least in the short term. Yet, the maintenance of the status quo should not be viewed as a reason for celebration within the anti-hunger community. Instead, it begs the question: Who wins and who loses with the current situation? For anti-hunger groups, the absence of what they perceive to be demeaning restrictions can be seen as a symbolic victory for the way America views the decision-making ability of the poor. From an economic angle, the beverage industry comes up as the big winner. No policy changes translate into their continued ability to sell billions of dollars’ worth of SSBs every year through the SNAP program.

The big loser is the health of SNAP recipients, whose continued high levels of soda consumption leads them, like many other low-income Americans, toward obesity, diabetes, and other related maladies. This business as usual approach injures not just their bodies, but also their spirits. In the words of one Oregon health care professional I spoke with, “Where’s the dignity in having diabetes and being 150 pounds overweight?”

Dire hunger no longer stalks this country in large measure due to the food stamp program and other federal food assistance programs. This fact does not trivialize the continued existence of food insecurity or the severe health consequences, especially to children, that accompany it. Yet the poor increasingly suffer from high rates of chronic diseases caused by overnutrition, such as obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Anti-hunger advocates and the beverage industry often frame their opposition in abstract terms of the loss of the cherished value of freedom of choice, a foundational principle of our society and market economy. But as the Johns Hopkins University bioethicist Nancy Kass has keenly observed, we all make food choices within established parameters. Our consumption behavior is not free at all, she notes in a 2014 American Journal of Public Health article, but constrained by the environment in which we live. Access, location, and even our meal companions all affect our dietary choices. Similarly, the external environment through marketing (such as store-level signage and product placement) and advertising affects our ability to make healthy choices.

The public goes grocery shopping within a food system that generates enormous amounts of collateral damage in the form of ever-increasing rates of diet-related diseases. SNAP has been designed to follow the marketplace, seeking to normalize the way in which the poor acquire food. In shifting food assistance away from commodity distributions and other stigmatizing methods, SNAP has made great strides. Yet being downstream to a disease-producing system is no picnic either.

Redefining the nation’s nutrition safety net so that Jim Weill and Walter Willett can work together toward a common vision of SNAP will require both political realignment as well as some coming to Jesus moments for both the public health and anti-hunger communities. The journey, if taken, will be long and arduous, filled with twists and turns and political pitfalls. It will require new partners, new funding sources, and new ways of measuring success.

“The time has come for a strategic, coordinated, public health-driven strategy for SNAP,” said Walter Willett in 2012, following the release of a monumental report on SNAP presented at a congressional hearing. “To not move in this direction is an enormous missed opportunity to meet two dire needs in this country — food insecurity and obesity — in one fell swoop.” Nearly a decade later, that challenge remains unmet.

Andrew Fisher has worked in the anti-hunger field for 25 years, as the executive director of national and local food groups, and as a researcher, organizer, policy advocate, and coalition builder. He is the author of “Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups,” from which this article is adapted.