“By destroying an idea, you actually make progress”: In Conversation With Paul Nurse

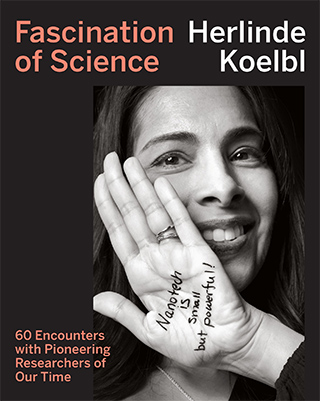

What makes a brilliant scientist? Who are the people behind the greatest discoveries of our time? Connecting art and science, photographer Herlinde Koelbl seeks the answers in her book “Fascination of Science,” an indelible collection of portraits of and interviews with 60 pioneering scientists of the 21st century. Koelbl’s approach is intimate and accessible, and her highly personal interviews with her subjects reveal the forces (as well as the personal quirks) that motivate the scientists’ work.

“I wanted to know how they think and with what insights they influence our lives, our future,” writes Koelbl in the book’s preface. “To this end, I traveled halfway around the world to ‘research’ these top scientists and to pass on their fascinating scientific results and life experiences — in other words, to bring science to life.”

Throughout August, we’re featuring one interview from the book each week. This week, Koelbl chats with Paul Nurse, Director of the Francis Crick Institute and winner, with Leland Hartwell and Tim Hunt, of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discoveries concerning the regulation of the cell cycle.

Other interviews in the Fascination of Science series include:

AUGUST 1st: Frances Arnold / A pioneer in the field of “directed evolution,” a genetic engineering acceleration of random mutations, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2018. Read the discussion here.

AUGUST 14th: Tolullah Oni / Public Health Physician scientist and urban epidemiologist, who seeks to improve public health systems and address external influences on the health of urban populations. Read the discussion here.

AUGUST 21st: Françoise Barré-Sinoussi / Virologist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2008 for her contributions to HIV/AIDS research and as a co-discoverer of HIV. Read the discussion here.

—The Editors

Dr. Nurse, you’re known for having wide interests. For example, you’ve compared doing science to reading a good poem. What did you mean by that exactly?

Well, science is quite tough, and doing research is even tougher because you’re at the cutting edge of knowledge — which means you often fail, and you’re often walking in a fog. But sometimes the fog clears, and it’s that clarity that I liken to a poem. When you read some poetry, suddenly you have a different view of the world — you understand something better — and science can be like that.

Surely it’s not every scientist who reads poetry?

Well, I can only speak for myself. I do have wide interests, and I’ve done many other things. I’m a pilot, for example; I fly airplanes and gliders. And I like walking in the mountains. I’m interested in theater and museums, and I’m a trustee at the British Museum. Actually, I wouldn’t mind having a bit more time for those other interests. My family says I work too hard, and that’s probably true. This morning I was up at five, doing a couple of hours’ work before breakfast, for example. But it’s enjoyable work.

You once said that as soon as you entered university, you knew you wanted to become a scientist. How did you know?

Yes, it’s true. When I went to university, I was 18 years old and suddenly the whole world opened up in front of me. I was being exposed to all sorts of things I had never thought about before, and I found this enormously stimulating. I mean, it wasn’t just the sciences — it was also the humanities, the arts, culture, the social sciences. And it’s probably that diversity that set me up for the rest of my life. I felt it was a privilege to be where I could learn about the world. And indeed, it’s been a privilege all my life that people have hired me to satisfy my curiosity. I mean, it’s almost unbelievable to me that I could be paid to do just exactly what I want to do!

Tell me about your background. What kind of family did you grow up in?

I came from a working-class, blue-collar family. So, it wasn’t an academic background. There was nothing problematic about it, but I hadn’t been exposed to books, to ideas, to culture.

Was your family religious?

Yes, I was brought up in a home that was Baptist. I went to Sunday school, and I was a committed believer. I thought I might even become a preacher! But I got exposed to more of the world at school, and when I learned about evolution, the minister was not happy about the things I was asking him. I remember saying, “Can we not think of Genesis as a metaphor?” He just couldn’t cope with that.

“I failed an entrance examination in French six times. Not once, not twice, but six times.”

That made me begin to doubt, and gradually I moved into my present position as a skeptical agnostic. An atheist is somebody who knows there is no God and no supernatural being. A skeptical agnostic is somebody who thinks it’s very unlikely, but because it’s supernatural and therefore beyond our understanding, how can you be sure?

You didn’t go directly from high school to university, is that right?

Yes, that’s true. I failed an entrance examination in French six times. Not once, not twice, but six times. I was trying desperately hard, and I couldn’t pass! This was the late 1960s, and at the time that meant I could not get into any university in the UK.

That must have been quite a blow.

It was difficult, but in hindsight it was actually useful. I worked as a technician in the local Guinness Brewery, and that was important for me because I had a year of experience working in laboratories, which only strengthened my wish to work in that kind of environment.

And that break was critical for me for another reason. I had failed early in my life, so I was no longer frightened of failure. I have many excellent graduate students who experience setbacks in their work, and it’s quite difficult for them psychologically. Because I had failed so early, accepting failure was no problem for me.

Speaking of failure, I heard that your student experiment with fish eggs didn’t go very well. Can you talk about that?

Yes, yes! My project was to measure the respiration in dividing fish eggs. We put them in a bath that had an instrument to keep the temperature constant. Those fish eggs were dividing from one to two to four. I was measuring their breathing, and I concluded that they were changing their respiration rate. But it wasn’t true! The change in rate had nothing to do with the dividing eggs, and it had everything to do with the thermostat on the water bath turning itself on and off. I found this out only at the very end of the project.

When you have a setback like that, does it cause you to have doubts about your calling?

Well, at the time I did think, Maybe I’m no good at this. Maybe it’s not for me. And at one point, I thought I should do philosophy or history of science. In fact, I contacted the London School of Economics. Karl Popper was there, a very important philosopher of science. So, I read a couple of Popper’s books, and these helped me plan my experiments better. Popper said to take observations, make a clear hypothesis, and then test the hypothesis to try and destroy it. In other words, by destroying an idea, you actually make progress.

So, reading Karl Popper’s books helped persuade you to stick with science?

Yes, it changed my mind that maybe I wasn’t a failure! But also, I was working in a small group at that time, and I was having limited conversations with others. Doing science is difficult, and you need help. Having a good collegiate culture in a laboratory is important to get people through those difficult patches.

“Science isn’t just about producing papers for big, fancy journals. It is in fact the pursuit of truth, and sometimes that truth will be difficult to accept.”

Science is a high calling. It isn’t just about producing papers for big, fancy journals. It is in fact the pursuit of truth, and sometimes that truth will be difficult to accept. Sometimes your hypotheses and ideas are dashed, but you must always remember it’s the pursuit of truth. It’s a high calling, and it should be seen as such.

I would imagine there’s a lot of rivalry between scientists?

Yes, that’s an interesting point. Science is both collaborative and individualistic. Of course, no person is an island, and even if you’re a novelist working alone, you’re influenced by the culture around you. Isaac Newton said, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” He recognized that he was part of a community — though he was an arrogant, unpleasant person, it turns out!

In any case, if I’m doing a project that I know others are also doing, and all that matters is the competition to see who gets there first, I ask myself, Why on earth am I doing this? I’d rather do something where I and my colleagues have time to think and to experiment.

And once you began working as a scientist, you moved around quite a lot, correct?

Yes, I had to move to different places to stay employed. I worked for a while in Edinburgh and at the University of Sussex. Changing situations exposes you to different things. When you move, you become a baby again, with everything around you new. I sometimes think of Trotsky, who said you should break things up and reassemble them and look at them afresh.

Changing jobs frequently must have carried a lot of uncertainty, though?

Not uncertainty, but it’s not knowing where the next year’s salary might come from. In academia today, young people often worry about salary. But for some reason, I didn’t worry about that. It may be that I’m a complete optimist, and it may be because I was so interested in what I wanted to do that I was prepared to tolerate the insecurity that went along with it.

What was it like to set up your first lab?

When I was a postdoctoral worker, I spent time in two laboratories, in Bern and in Edinburgh, and they both gave me a lot of freedom. Even though I was in somebody else’s lab, I had a lot of control over what I did. So, by the time I was about 30 and setting up my own lab at the University of Sussex in Brighton, I was already used to running things. What I wasn’t used to was establishing the infrastructure and raising money, so I had to learn that.

And what were you working on at that time?

What I was working on isn’t so different from the problem I’m still interested in. We’re all made of cells — billions and billions of cells; that’s the basic unit of life. And growth and reproduction come from the division of one cell into two cells. I’ve devoted most of my life to determining what controls the reproduction of the cell and its subsequent division.

In fact, when you were awarded the Nobel Prize, it was for your discovery of protein molecules that control the division of cells. I imagine this was your greatest finding, no?

It was indeed the main discovery of my life, though in fact I’m still working on this topic because there remain things we need to know. But yes, what we discovered — my colleagues and myself, and also Lee Hartwell and Tim Hunt — was that there’s a complex of molecules that make an enzyme, and this enzyme adds phosphate to other proteins. This can act as an important switch for different events in the cell.

Can you say more about the consequences of that discovery?

It meant that we now understood the basic process that controls growth and reproduction in the cells — in other words, the process that underpins growth and reproduction. Not just in humans but also in all every animal and plant you can see around you. And this has many applications, including those for cancer research.

You’ve also been knighted by the Queen. That must have been quite an experience?

It came as a shock, actually! In fact, the letter asking whether I would accept the knighthood was sent to the wrong address, so I never received it. Then one day, I had a call from 10 Downing Street, asking if it was my intention to refuse the honor? And I said, “I’m sorry, but I have no idea what honor you’re talking about!”

It was about 10 o’clock on a Friday morning, and I responded that I needed to think about it over the weekend, but they said, “You have until 4 o’clock this afternoon.” All right, so I phoned my family to talk it over, and they said of course you should accept it. And so, I did. Then they sent the invitation to the Palace also to the wrong address, so I nearly didn’t get to the ceremony, either. I also received the Ordre national de la Légion d’honneur from France, and you may remember I failed the French O-level six times. I had to give a little speech in French, which was terrible, of course!

Receiving these awards must have been quite satisfying?

Well, yes. I don’t think I’m vain, to be honest, but of course one is pleased to be knighted. And I’ve won quite a number of awards. The main satisfaction, however, has been in helping to understand how the division of cells is controlled. That’s really what the honor is for me.

What would you like your message to the world to be?

I would like the world to be a more rational and forgiving and tolerant place, and I think science can contribute to that. Science is essentially a rational activity. We should learn from the values of the Enlightenment, and we should apply them, including a tolerance of other people’s thinking and thoughts. At the Francis Crick Institute, 70 percent of our scientists are from other countries, and any change to that means we’re not utilizing the intellectual capital in the world. We need an openness to the world. Brexit, unfortunately, just represents putting up barriers, and those barriers will break down the values of science.

“I would like the world to be a more rational and forgiving and tolerant place, and I think science can contribute to that.”

The community of scientists can be complacent. We are a bit of an odd lot, you know? Sometimes we’re a little remote, sometimes we behave in eccentric ways. Scientists think, Oh, I’m in my laboratory, I’m doing my investigation, just leave me alone, but that’s not good enough. We have to deal with the public, talk to them, and confront the issues if we’re going to keep the scientific endeavor working.

And with the advent of CRISPR and other methods, there are ethical questions that need to be addressed, yes?

Absolutely. Now with medicine, we can do things we couldn’t conceive of 30 or 40 years ago. What right have we to manipulate the genome? There’s still huge opposition to this, particularly in parts of continental Europe, but we are producing ways of changing the world through science that need to be fully discussed, to see whether we should apply them or not. We have to do it early on, and we have to be, in some respects, humble about it.

And that does not apply just to scientists: it’s a social science problem, it’s a religious problem sometimes. Different cultures and different societies may come to different answers to this question. But the only way forward is to be open, try to apply rational argument, and consider the evidence in order to come to satisfactory solutions for all people.

In 2003, you were president of Rockefeller University in New York, and you discovered something about your family history that changed your world completely. What was that?

Since I was living in the United States, I applied for a green card. The application was rejected because there was an issue with my birth certificate. When I got hold of a more complete birth certificate, I discovered that my mother was not my mother — she was my grandmother, and my real mother was the woman I knew as my sister.

Now, I hadn’t known any of this. What happened was that my mother got pregnant at age 17, and she wasn’t married. She was sent away to live with her aunt in Norwich, England, where she gave birth to me. My grandmother then pretended she was the mother of the child. The whole thing was kept secret. This wasn’t so unusual at the time — the early 1950s — because illegitimacy was a big shame. It’s nearly impossible to imagine today, and it was a bit of a shock.

Only a bit?

No, it was a big shock. I mean, of course, that my parents were somewhat elderly, and I would say, “It’s like being brought up by my grandparents.” Little did I know I was actually being brought up by my grandparents.

How did you fit into your family otherwise?

Well, I went to university, and nobody had ever been to university. There were differences between us, and I couldn’t quite explain them. I’m a geneticist, remember, and what’s amusing is that my own genetics was completely unknown to me. Anyway, my family did their best. My grandparents took me into their care when they were in their forties and never complained about it. My mother was devastated, I’m sure, having to give up her child and leave home. She then married when I was two and a half. She lived nearby and used to come and visit every week. She died before I found this out, as had my grandparents and nearly everybody in the family. It didn’t disturb me very much at the time.

No?

My life was okay. It was normal. I was loved by my parents — my grandparents. Now, of course, with DNA, it could be that I’ll discover who my father is.

Are you curious?

I am, maybe because I’m a geneticist. I’m curious about where half my genes came from. I’m not obsessed with it, but I’m curious.

Herlinde Koelbl is a German photographic artist, author, and documentary filmmaker. She has published more than a dozen photography books and has received numerous awards for her work, including the Dr. Erich Salomon Prize in 2001. You can learn more about her at www.herlindekoelbl.com. This interview is excerpted from her book “Fascination of Science.”