Henrietta Leavitt Expanded Our Universe

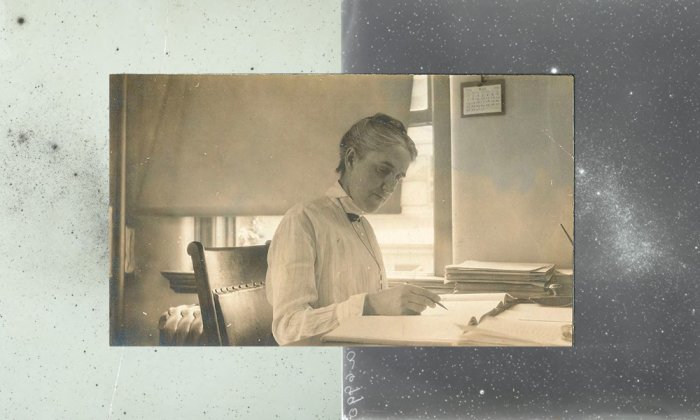

Henrietta Leavitt worked at the Harvard College Observatory from the turn of the 20th century until her death in 1921. She sat at her desk studying photographs of the night sky — thousands of glass plates that had been coated with a light-sensitive emulsion and exposed to starlight through a telescope’s lens. Most were photographic negatives: Each star registered as a speck of emulsion; each plate was a suspension of myriad black dots. Leavitt discovered the period-luminosity relation, which provided astronomers the first means to measure the distance to faraway stars. Before her discovery our imagined universe was flat. There was no sense of depth to the stars, no ability to know where we were in space. Leavitt changed all of this. From a two-dimensional surface, Leavitt revealed an unimaginably vast three-dimensional universe and defined our place in it.

What follows is an excerpt from Anna Von Mertens’s layered portrait of astronomer Henrietta Leavitt, “Attention Is Discovery.” The piece is situated at the center of the book, amid essays on Leavitt’s inventive methodologies, her groundbreaking discovery, its cultural context, and its contemporary scientific relevance. Titled “Name and Present Occupation,” it examines the monikers and job titles placed on Leavitt and considers her rightful place in the scientific canon alongside what Leavitt’s own inclination might have been.

There are times when I use the name Henrietta. In my studio, spending hours at my desk drawing, hours sitting and sewing, her first name surfaces. Repetition — a stitch, a mark, a comma, a choice, a strikethrough — creates intimacy. (When John Kramer and I were finalizing all of the details for the Harvard Radcliffe Institute’s “Measure” catalog, we definitely used the name Henrietta.) Among all the colleagues who became friends, Henrietta became one, too. Then again, she might ask: Who the heck are you? In many ways, Henrietta, but not in all ways, I am a stranger.

She was addressed as Miss Leavitt by her colleagues, a name respectfully formal yet softened by closeness. This was important work, and it was treated as such.

“H. S. L.” is how she asserted her presence in her logbooks, or marked ownership on clarifications that sometimes appear on the manila envelopes sheathing the precious glass plates — a guideline or remark for the next woman pulling that particular plate from the stacks. When her initials appear, there is a period after each letter, always. Once I came across a rare notation on one of the glass plates that included those three letters in red ink, a period after each one. Each dot had the same circumference — a result of her knowing the exact distance needed to bring her pen to glass. Oh, the steadiness of her hand!

Her full name stretches out: Henrietta Swan Leavitt. Evocative, yes, but that added word feels unnecessary. I don’t know Edwin Hubble’s middle name. Twice I have looked it up and promptly forgotten it. Encyclopedic entries tend to state his name plainly: Edwin Hubble. I notice that for Henrietta Leavitt, biographical summaries can’t seem to resist inserting that Swan. It sends my mind to Cygnus the Swan (our Northern Cross), and within that constellation the X ray binary of a supergiant and an unseen black hole in a perpetual do-si-do that made two famous scientists place a famous bet. With Swan, it’s easy to get carried away.

In Gala Bent’s poem: unless we dive out into / Henrietta’s middle name. It’s a poem that sings the songs of women’s names that deserve to be sung. In the first line is the name of another scientist who ignored distractions — internal, external — and did the work: Vera! Vera Rubin! (How adjacent is Hubble’s “VAR!”)

In the index of a book about how our modern universe became known, a single page number is listed under “Leavitt, Henrietta.” When I turn to that page, I find 26 words describing her accomplishments. In another book on cosmology (also to remain nameless), I see “Hubble’s Cepheids.” I get protective. Those are Leavitt’s Cepheids. She understood them better than anyone else.

Recently I heard a reference to Hubble, the man, in an interview, and in the next sentence Hubble, the telescope, without clarification. The Hubble constant is measured to understand the expansion of space, our cosmic acceleration. Now there is the Hubble tension, the discrepancy between methods for how that expansion rate is calculated. Hubble’s name has been condensed to one word, yet is expansively synonymous. Think what Leavitt could become.

There is another consideration: What word to use for her job, her life’s work? The historical term applied to Leavitt and her colleagues based on their original job description, the Harvard Computers, in many ways feels right. A bunch of women sitting around doing math. But it does not acknowledge their individual roles at the observatory, the varied lines of research, or the singular reflections and preferences in the Brick Building.

Williamina Paton Fleming was born on May 15, 1857, and died on May 21, 1911. Carved into her gravestone is only one additional word: ASTRONOMER.

This is also the word Fleming chose to describe herself in life, evidenced by her 1907 petition for naturalization. (Present for the occasion were Harvard College Observatory director Edward Pickering and astronomer Solon Bailey — her observatory family — as signing witnesses.) To complete the line “My occupation is,” Fleming wrote, “Astronomer.”

In a 1908 Oberlin College alumni survey to inform its Anniversary Catalogue of Former Students, one line reads: “Present occupation?” The inclusion of a question mark is almost quaint. Leavitt answered “Astronomical Research,” as if in wondering what title to take on she decided instead to write the subject of her study. In the year before her death, Leavitt was living with her widowed mother in an apartment near the observatory. On the 1920 United States census form her mother is listed as the head of the household, followed by “Henrietta S., daughter.” Under the header “Trade, profession, or particular kind of work done, as spinner, salesman, laborer, etc.” — among the many answers like teacher, maid, salesman, clerk — is that surprising yet obvious word: astronomer.

We can easily designate Leavitt an astronomer, the woman who helped us place the stars. But I like staying for a moment in the ambiguity of her answer to the Oberlin survey. There, in the middle of things, I see Leavitt’s word research as a verb, not a noun. She investigated. Leavitt cared about the work; she dedicated her life to it. Like the faithful placement of dots between her initials and the pursuit of faint stars, it was the work — the action of it — that seems to have been most important to Henrietta.

Anna Von Mertens is the author of “Attention is Discovery: The Life and Legacy of Astronomer Henrietta Leavitt,” from which this article is adapted. She is the recipient of a 2010 United States Artists Fellowship in Visual Arts and a 2021–2022 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.