Reproductive Justice Is for Everybody: In Conversation With Donna J. Drucker

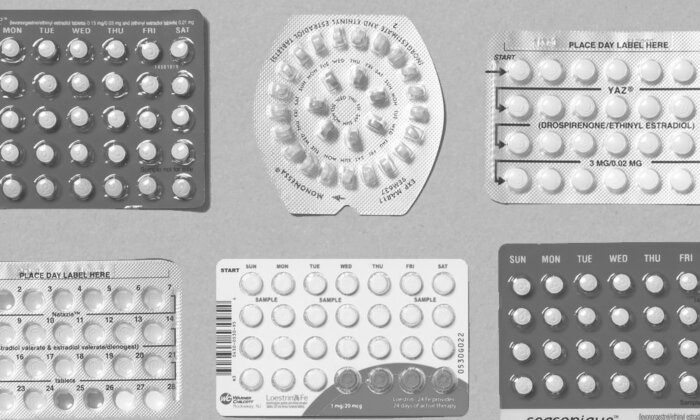

When most of us think of the technologies that have transformed modern society, we think of the mechanical or industrial — the railway, the television, the internet. And while these technologies have undoubtedly shaped contemporary life, we would do well to hold medicinal and pharmacological technologies in mind too. The impacts of reproductive technologies, for example, are far-reaching and complex. As Donna J. Drucker writes in her book “Contraception: A Concise History,” the history of contraception can be framed in a “wider context of population control, eugenics (including involuntary sterilization), racist and classist restrictions on birth control access, and the extent to which people do or do not accept technological methods into their sexual and reproductive lives.” Indeed, contraceptive technologies — and the laws surrounding them — have reshaped human reproduction and sexuality and have profoundly affected people’s personal lives.

For this episode of the MIT Press podcast, I spoke with Donna about the development, manufacturing, and use of contraceptive methods from the late 19th century to the present, as well as what the contraceptive industry holds in store. A stream and lightly edited transcript of the podcast can be found below.

Sam Kelly: Hi, Donna. Thanks for speaking to me today.

Donna J. Drucker: Hi, thanks for having me on.

SK: You’re the senior advisor in English as the Language of Instruction at TU Darmstadt in Germany, and the author of “A Classification of Sex: Alfred Kinsey and the Organization of Knowledge, “The Machines of Sex Research: Technology and the Politics of Identity 1945 to 1985,” and of course “Contraception: A Concise History,” which was published as part of the Essential Knowledge series in April here at MIT Press.

I read your book on a train to Manchester this weekend. These trains have screens that cycle through BBC headlines and one of them read, quite fittingly, “Contraception shortages causing utter chaos.” So perhaps a good place to start is by asking if you could explain how contraceptive technology has ordered society historically and how it continues to do so now?

DD: Great question, and it would take a lifetime to answer it fully, but I can give it a shot. I think access to contraception goes to some fundamental questions about how we as a society decide who gets to reproduce and who doesn’t. Who gets to bring forth children and who doesn’t?

For example, the restrictions around technology are one part of the story whilst allowing access and innovation are another part. There’s also the legal dimension, as well as medical and history. In addition to that you have to remain sensitive to geographic and governmental contexts.

We can look at contraception in the United States as an example, since a lot of listeners will be familiar with American history. In the U.S. it was declared illegal to distribute, buy or sell contraception in 1873 under the Comstock Act. Although you could still get it, you would have to sell it or buy it under different kinds of guises, different sorts of use, different sorts of language to get access to it, which brought forth a tremendous underground market for devices. At this time, the term devices refered to condoms, diaphragms, cervical caps, some spermicides, things like that.

I think access to contraception goes to some fundamental questions about how we as a society decide who gets to reproduce and who doesn’t.

It’s not until the 1930s, specifically 1936, when contraception in the U.S. is legally prescribable by physicians. That’s due to a long legal fight put forward initially by a physician in Margaret Sanger’s birth control research bureau. Whilst that didn’t necessarily have a massive impact on society (since there was still plenty of access to contraception) this illustrates that by the 1930s the dissonance between the popular usage and the social rules governing particular technologies.

Moving on through the 20th century, the next major technological advance in contraception is of course the hormonal pill, which was first legalized in the U.S. in 1957 for menstrual disorders. By 1960 it’s okay for physicians to prescribe it for married women. Then it takes off around the world under lots of different names, manufactured by various companies, not quite immediately but quickly. In this period between the Comstock Act and the development of the pill, there are enormous social changes. In that period of 90 years, contraception shifts the balance of power over who decides who gets to use contraception. What ends up happening after the pill becomes widely available is that within a period of about two years, the agency shifts away from men, who traditionally had the physical method (i.e., withdrawal, or the technical method of condoms) to control when a pregnancy could potentially occur.

SK: The position you take up in the book is one that places a great deal of importance on ‘reproductive justice.’ Could you define that term?

DD: I think there are three concepts that are important in thinking not only about contraception but about the broad range of reproductive-related technologies. Those are reproductive health, which is a service delivery to individual women. Reproductive rights, which are the legal rights to reproductive healthcare, including abortion. Then there’s reproductive justice, which was a term developed in the mid-1990s by African American women and it’s really a framework that identifies how reproductive oppression is the result of the intersection of multiple oppressions and is connected to the broader struggle for social justice and human rights.

Reproductive justice focuses specifically on three simple sounding but rather complex rights, which are first, the right to have a child, second, the right not to have a child, and third, the right to parent. Reproductive rights advocates measure laws and policies along these three metrics. What’s helpful is it doesn’t just take reproductive rights as a form of analysis, but a broader sense of human justice and bodily autonomy.

The interesting thing, as you said, is that this form of analysis can help us examine whether a technology is harmful for people or genuinely helpful. It’s important to remember that national governments all around the world have specific interests in how large their population is, how healthy their population is, and governments sometimes want to promote the number of children that exist in a country and sometimes they want to limit that number.

The rule was that the number of children that you had multiplied by your age had to be over 120 before you were eligible for sterilization.

One example of using the notion of reproductive justice to think through a problem is the emergency in India during 1975-77. Part of this emergency was a new set of laws and rules that demanded people be sterilized in order to receive particular government services or to be eligible for certain government services. For example, if a man had six children and he wanted to get a bank loan, he would have to prove to the bank that he was sterilized in order to get the loan. Of course, that’s a significant form of reproductive coercion, to link your fertility to something like a bank loan.

Reproductive justice can help us analyze the different ways that a single technology, like sterilization, can be used both to curtail human rights and also be used to promote human rights in that sometimes people really want sterilization or they want a particular kind of service and they’re denied it for other reasons.

On the other side, in the United States in the 1970s there were battles on the other side of sterilization, in that a lot of white women wanted to be sterilized after having perhaps two or three children, and they were stymied from doing that due to hospital regulations that were often referred to as the ‘120 rule.’ The rule was that the number of children that you had multiplied by your age had to be over 120 before you were eligible for sterilization.

SK: Do you know how that number was arrived at?

DD: I don’t know that one specifically. I think it was 100 in some places, perhaps 150 in others. It was really just a mechanism to ensure that white women had done their breeding duty to society and had a sufficient number of children before they were allowed to have an operation that they wanted. It’s easy to see how you can use reproductive justice to investigate a single technology and evaluate both its coercive elements and its freeing elements at the same time.

SK: Contraception as a field of study is so intertangled with the dynamics of gender, sexuality, colonialism and class. But it’s also something that might not always occur as such a political subject.

DD: Yeah, that’s right. That’s right.

SK: Would you be able to tell me a little bit about your thoughts on the future of contraception? How can we make sure that contraceptive technology is designed and implemented in a way that furthers reproductive justice, in tandem with society’s developing understanding of gender and sexuality?

DD: At the moment, there are a variety of different kinds of technologies and medical experiments happening. For the last 150 years, contraceptive testing has taken place more or less along the same two axes, either medical technologies (the pill) or physical barrier technologies (condoms and diaphragms).

People continue to tinker with the physical ones, for example, the diaphragm and the cervical cap have come back into fashion slightly. The female condom, which has now been renamed the internal condom, has made a return, particularly in Subsaharan Africa. There continues to be developments along the lines of which kinds of materials work best for barrier methods, what inspires people to use them, to buy them, to take them on and so on.

On the other side, there continue to be medical, particularly hormonal, technologies under development. Some of them have only been tested on mice. A lot of them are being tested on men, because there are a number of men who do want to take an active responsibility for contraception outside of making sure they use a barrier method. The one that is best known was on trial between 2008 and 2012, but it was canceled due to men’s strong reactions to side effects. These included typical experiences for women on the pill, such as headaches, bloating, weight gain and irritability etc. That study didn’t proceed any further, but there will still continue to be people working with hormones and different hormone formulations to see which ones can be used with the least side effects.

In the future, what I think is striking is that the contraceptive industry and public health advocates and researchers around the world are really engaged in developing contraceptives that are workable for everybody. Those include people who are obese or severely obese, who may have difficulties absorbing the hormones in a pill.

It’s also of particular concern for people who are transgender. For example, someone transitioning from a female-oriented body to a male-oriented body may want to use contraception but they can’t use an IUD because their vagina won’t hold the IUD fast within it. So there’s more and more attention to providing health care for people with a wider range of bodies, a wider range of physical concerns so that everyone who wants to prevent a pregnancy is able to, healthfully and safely.

SK: What a wonderful sentiment to end with. Thank you so much for coming and speaking to me today.