Stalin’s Architect: The Remarkable Life of Boris Iofan

“Poetry might survive in a totalitarian age, and certain arts or half-arts, such as architecture, might even find tyranny beneficial, but the prose writer would have no choice between silence or death.”

–George Orwell

For Boris Iofan, the most prominent of Stalin’s architects, the patronage of a murderous dictator came at serious personal risk — as much to his critical reputation as to his life. Rather than not build at all, he was prepared to build what the dictator demanded of him. As a result, Iofan is now remembered not for his considerable talent, but for the way that his buildings came to define Stalinist architecture as it was practiced from Warsaw to Beijing.

Ever since the summer of 2008, when I visited his former apartment on the top floor of Moscow’s famous House on the Embankment, I have been unable to get Boris Iofan out of my mind. The House — which is in fact a large complex with more than 500 flats and its own cinema, theatre and department store — was one of his most significant projects.

Iofan’s apartment had hardly been touched since his death 30 years earlier. From its windows I could see the golden domes of the new Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a replica of the historic church destroyed by Stalin in 1931 to make room for the Palace of the Soviets. Iofan had watched the demolition of the original cathedral from this same window. In these rooms, surrounded by friends and colleagues — many of whom would soon be murdered by Stalin — he had celebrated his victory in the competition to design the palace, which he intended to be the world’s tallest building. Later, he watched a perfect circle of giant cranes rise on its construction site like a hollow crown, in a futile struggle to drag his reluctant building up from the mud. When the German army threatened Moscow in 1941, the crown imploded and the site went quiet; it remained so for a decade after the war. All Iofan’s hopes for the project were finally drowned when Nikita Khrushchev had the palace foundation pit flooded to create a huge open-air swimming pool. Iofan did not live to see the reappearance of the cathedral.

Except perhaps for Minoru Yamasaki and his World Trade Center in Manhattan, no architect of the 20th century has designed a structure that has become more politically charged with meaning, or that has come to play such an important part in a country’s history and culture. But while the Twin Towers were immolated, Iofan’s House on the Embankment survived, even as so many of its residents fell victim to Stalin’s violence.

The apartment had the smell of years of neglect. A plastic shower curtain had been slung over boxes of Iofan’s papers, but it did little to protect them from the dust generated by workmen attempting to modernize the kitchen. Under his desk was a plaster maquette of the Lenin statue he had designed to stand atop the Palace of the Soviets. On a table was another of a worker, right arm raised over his head in a conscious paraphrase of the Statue of Liberty: this had formed the basis for a huge stainless steel figure that topped the Soviet pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, an incongruous tribute to the proletarian revolution in Queens.

I found sheaves of black-edged official envelopes in a box. Among them was a telegram marked “SECRET” from Vyacheslav Molotov, dispatching Iofan to Stalingrad in a military transport plane immediately after the surrender of the German forces to advise on the reconstruction of a city that had been all but destroyed. Nearby were stacks of photograph albums; in one, an image of Iofan and his aristocratic half-Italian wife Olga, daughter of a Russian princess, taking tea with Frank Lloyd Wright at a conference in Moscow. In this picture Iofan appears a sympathetic, sensitive-featured man in his mid-40s, hair combed back from a high forehead. His wife, with a cigarette in her hand and a briefcase under her arm, looks animated, an equal partner in the conversation with the notoriously egotistical Wright.

After this visit, I began trying to learn as much as I could about what had gone on in Iofan’s mind as he saw his work turned into a monstrous tribute to Stalin — as much as it is ever possible to know about the internal lives of others. I tried to piece together all the disparate elements, the surviving objects and records, in a way that made sense. Mostly I was driven by a desire to understand the part that architecture had played in the state apparatus of one of history’s most murderous regimes. But I was also drawn in by Iofan himself and the remarkable life that this stylishly dressed, distinguished figure — who looked disarmingly like my own father — had lived. I had spent six years studying architecture myself; what would I have done in Iofan’s place?

In the course of Iofan’s 45 years in this apartment, his bookshelves had filled up with volumes devoted to his own work as well as to that of the Renaissance masters he admired. His drawings of interiors for the Palace of the Soviets had been peeled away from his drawing board, to be framed and hung on the walls: no longer working documents, but fading memorials to what might have been. The chaotic mess of books, papers, fraternal greetings, medals, and ancient electrical appliances felt like the residue of an entire system — which is exactly what it was.

The chaotic mess of books, papers, fraternal greetings, medals, and ancient electrical appliances felt like the residue of an entire system — which is exactly what it was.

Outside, on that June day, Moscow was booming. A cascade of oil money was floating an armada of Prada stores where the more discreet customers left their bodyguards, dressed in camouflage uniforms, waiting on the pavement while they shopped. There were sushi restaurants with cellars full of Petrus, streets lined with Hummers with blacked-out windows. But the House on the Embankment smelled of sour decay. It was no longer the heart of the city.

As if in mockery of the red stars Stalin had impaled on the Kremlin spires across the river, the building was topped by a huge, revolving three-pointed Mercedes star — a relic of the wild excesses of the immediate post-communist period. That emblem has gone now, its removal ordered by Moscow’s mayor in 2011.

Things were very different in 1937, when Thomas Sgovio, a young and idealistic Italian American communist from upstate New York living in Moscow, visited Iofan in his apartment: number 426 on the sought-after top floor, facing the river. In those days many people in Moscow lived in miserably overcrowded conditions, sometimes went hungry, and were dressed mostly in worn-out clothing and shoes patched together with scraps of sacking. Inside the House on the Embankment was a cocoon of what would have seemed to them like unimaginable luxury.

Sgovio was hoping for Iofan’s help in securing a place at one of Moscow’s art schools. They had been introduced by a mutual acquaintance who knew Iofan from his own time as a student in Rome. Sgovio was baffled by the process of finding his way to the Iofans’ apartment in such an enormous building with so many entrances. He had to produce a special permit, leave his passport at the guard post and follow an official escort to the lift. From there, an attendant took him up to the 11th floor. A maid let him into the apartment and he was welcomed by Olga, a stately-looking woman who spoke in perfect English and offered him tea. Then Iofan himself appeared, the streaks of white in his dark hair adding a distinguished touch to his appearance.

Sgovio had been horrified by his experiences of everyday life in Moscow. When he ate in a workers’ canteen, the scraps of food he left on his plate were grabbed from him by hungry neighbors. It was not what he had expected from the world’s first socialist country. The Iofans’ home felt like an entirely different world, and he was charmed by their kindness. He also remembered noticing that Iofan’s clothes “were foreign-made — grey tweed slacks, black sleeveless sweater, white shirt, brown Oxfords with thick sponge soles — which gave him a youthful appearance.”

After tea, Iofan invited Sgovio into the studio and settled down to examine his portfolio of drawings. He looked at them carefully and commented politely, handing them to Olga for her to see the work for herself. Standing in the center of the room, which had skylights and a view of the river, was a model of the Palace of the Soviets. Was this the actual model chosen by Stalin, Sgovio asked? Iofan laughed. “No, that one is even larger. This is my personal working model.”

They talked about New York, a city Iofan had recently visited. He told Sgovio that he did not think much of modern American architecture: “It represents an ugly expression of capitalism. The skyscrapers are tall, rectangular boxes, made of shiny steel and stone, made to hide the ghettos of the poor beneath them. This is the architecture of the rich, eh? There is no spaciousness, no room to breathe.”

As Iofan showed him the model of the palace, Sgovio recalls him saying: “You see what I mean about spaciousness. The Palace of the Soviets will be the tallest building in the world. The radius of the base is more than its height. Can you imagine the capitalists building something like this in New York? The land on which it would stand costs millions, perhaps billions. It would take centuries for them to capitalize on the cost of the land alone. Here the land belongs to the people, and the Palace of the Soviets will belong to the people.”

Sgovio never did go to art school; he was arrested by the secret police at the gates of the American Embassy shortly after his meeting with Iofan. Convicted of being “a socially dangerous element,” he was sentenced to 16 years of forced labor. He survived a series of prison camps by using his artistic skills to draw tattoos for the criminals who were incarcerated alongside him. Many years later, back in America, he wrote an account of his disillusionment with communism — Iofan never had the chance to read it, but it might have prompted him to see some parallels with his own life story. Both men had joined the Communist Party out of conviction; both had chosen to move with their families to the Soviet Union; and both had used their talents as a means of staying alive.

Boris Mikhailovich Iofan died in 1976, the same year that “The House on the Embankment,” a bestselling novella by the Moscow writer Yuri Trifonov, was published. Iofan was 84 – a long life by any standards, but particularly impressive for the Soviet Union – and being cared for at Barvikha, a sanatorium he had built for the Communist Party elite nearly 50 years earlier.

“The House on the Embankment” is a lightly fictionalized account of the experiences of people living in Iofan’s austere complex of apartment blocks, located just across the river from the Kremlin. At the time he designed it, in the late 1920s — when the revolution was still a recent memory and an inspiration to many communists — it was known as Government House, and it would be home to most of the Soviet elite during the 1930s. Trifonov’s novella made such an impact that its title immediately became the building’s popular name, and today the House on the Embankment remains one of Moscow’s most prominent landmarks.

Iofan, his wife, two stepchildren and his younger sister Anna were among the first to take up residence in the House, moving in at the start of 1931. With the exception of two years when he was evacuated during the Great Patriotic War, he would live there for the rest of his life, sharing it with his stepdaughter after the deaths of his wife and his brother Dmitry in 1961.

Yuri Trifonov also lived in the House on the Embankment during the 1930s. He was present on the night that his father, who had been a hero of the Bolshevik revolution, was marched away to his death. Shortly afterwards, his mother was sent to a labor camp. Trifonov was just 12 years old at the time; she did not return until he was 20. Like many other victims of Stalin, the Trifonovs’ truncated lives are commemorated today in the line of wall plaques mounted near the entrances to the House. As many as 800 of their fellow residents — one-third of the people living there in 1932 — were eventually arrested by Stalin’s secret policemen, and more than 300 of them were shot.

“The House on the Embankment” captures the paranoiac mixture of privilege and fear felt by all those, including the Iofans, who lived in this “huge grey apartment house with its 1,000 windows giving it the look of a whole town.” Trifonov depicts a building patrolled by white-gloved militiamen, with all-seeing lift operators employed by the Ministry of the Interior guarding access to its apartments, on corridors that smelled of cooking. He portrays the anxiety of lives spent in the unspoken knowledge of secret listening rooms where policemen labored day and night, transcribing conversations relayed by microphones embedded in walls and listening in on telephone calls. Even as late as the 1970s, these things could not be discussed openly.

Trifonov portrays the anxiety of lives spent in the unspoken knowledge of secret listening rooms where policemen labored day and night, transcribing conversations relayed by microphones embedded in walls and listening in on telephone calls.

The novella examines the awkward relationship between the residents of the House, living in claustrophobic luxury, and those in its shadow who lacked everything. It illuminates the moral squalor of the endless compromises Stalin demanded of the Soviet elite, from admirals to philosophers to schoolchildren, politicians and architects. It exposes the jockeying for position and the emptiness of a society in which the ideology of the state is a weapon to be deployed in settling personal scores. It explores the political uses of privilege in a supposedly classless society.

“The House on the Embankment” first appeared in an issue of the literary monthly Druzhba narodov (Peoples’ Friendship), and later as a book. Many critics were amazed that it had been published at all, especially in a magazine with a reputation for taking, at least in Soviet terms, a culturally conservative position. There were some savage reviews by various orthodox defenders of the regime who would have preferred to see it sink without trace, but in spite of their efforts it was a huge success. Its acknowledgment of the psychological damage caused by decades of dishonest public rhetoric was like a gulp of life-saving oxygen in the stifling airlessness of Brezhnev’s Soviet Union.

It is impossible to know whether Boris Iofan read Trifonov’s book before he died. But he might well have encountered Trifonov as a child decades earlier, playing around the fountain in one of the building’s three courtyards. Contemporary accounts suggest that Iofan was an approachable and genial figure, ready to entertain the children of the building in his home. He and Olga had the luxury of an apartment spacious enough to accommodate Boris’s personal studio (his official studio was beside the Kremlin walls) and a live-in housekeeper. Before the war he kept his Buick convertible, purchased during a trip to the U.S. in 1934, in the garage beneath the building.

Elina Kisis, daughter of the party official I. R. Kisis, later recalled visiting Iofan as a 10-year-old. “During the day Boris Mikhailovich liked to work in his studio and I would often go and visit him there. He grew fond of me and used to show me beautiful pictures, books, and postcards, give me apples and pat me on the head. There for the first time I saw many things that we and others did not have. There were some dark, shiny figures and figurines (probably bronze, but also a few white marble ones) on tall stands. There were lots of paintings and other mysterious things. In the middle of the studio, on tripods, were some huge drawing boards with pictures of a tall building that looked like a Kremlin tower, with a man on top. ‘That’s Lenin,’ he said.”

In Trifonov’s book there is a character whose home has space to host 50 guests for a party and “corridors that feel like museum galleries.” Elsewhere, he describes priceless 19th-century Russian seascapes lining the walls of one apartment and plaster busts of great but politically suspect philosophers, “probably acquired in Berlin,” on the library shelves of another. He mentions the progressive-looking lampshades and the modernist government-issued furniture (designed by Iofan) in one of the more modest three-room apartments. Many other residents had the means to buy and install their own custom-made furniture, imported in at least one case from England.

Iofan would have clearly understood the dilemma that faced anyone for whom meeting the demands of Stalin and his enablers was the price of remaining in these apartments — even of staying alive. As a child, Trifonov’s protagonist, Vadim Aleksandrovich Glebov, in a fit of schoolboy hooligan envy persuades two of his friends to assault the son of a high-ranking NKVD officer living in the House on the Embankment. Later, Glebov reveals their names to the official, believing that he has no choice if he is to secure the officer’s help in arranging the release of a relative of his who has been arrested. His friends are never seen again — but Glebov’s relative stays in the gulag. As a graduate student after the war, Glebov is encouraged by the party cell at his university to inform on a professor suspected of so-called “cosmopolitanism.” The professor is not only a resident of the House on the Embankment, but is about to become Glebov’s father-in-law. What can Glebov do but comply, if he is to secure academic tenure after completing his doctorate? With no apparent difficulty he betrays his fiancée and her father, his teacher, for the sake of a safer and more comfortable life.

Iofan had to close his eyes while Stalin set his torturers to work on Aleksei Rykov, former premier of the Soviet Union and one of Iofan’s closest friends.

Iofan was himself accused of cosmopolitanism in 1949, and it cost him the chance to build Moscow State University; but 10 years earlier, he had an even more difficult challenge to deal with. He had to close his eyes while Stalin set his torturers to work on Aleksei Rykov, former premier of the Soviet Union and one of Iofan’s closest friends. It was Rykov, in fact, who had given Iofan the task of building the House on the Embankment, and the two had been neighbors there before his arrest.

It was not enough for Iofan simply to keep silent. The price he had to pay for designing the Palace of the Soviets — the most important building of his career, on which he began working even before the House on the Embankment was finished — was to keep up a continual stream of praise for the genius of Stalin. Even after Rykov’s judicial murder, Iofan declared: “Never before has an artist been able to devote himself in this way to an art that is placed at the service of the workers, at the service of a new and remarkable culture, the culture of a communist society – as now, in the era of the great Stalin.”

In his well-cut tweed suits and knitted ties, with his sensitive, watchful eyes, Iofan appeared to be the model of a liberal modern architect. However, he seems to have willingly declared his devotion to “the leader of peoples, the inspirer of all our victories, Comrade Stalin, who helped us to arrive at the final form of the Palace of Soviets. We live in the great era of joyous creative labor.” Iofan wrote his own speeches, so it seems reasonable to conclude that he was prepared to say whatever he needed to in order to stay alive. To this day, his surviving family members believe that despite everything, he always respected Stalin.

Iofan was not vindictive in the way of some of his contemporaries, such as Karo Alabyan, architect of the Red Army Theatre in Moscow with its notorious floor plan in the form of a five-pointed Soviet star. Alabyan’s campaign against those he claimed were Trotskyite architects and Gestapo agents led directly to the death of Mikhail Okhitovich, a visionary urban theorist who was arrested and executed as a result of his denunciation. Alabyan was equally eager to destroy the career of the prodigiously gifted Ivan Leonidov; and there almost certainly were other victims.

But although Iofan did not betray his friend Rykov — and indeed seems to have made an effort to help Rykov’s daughter when she was subsequently imprisoned in a labor camp — he remained loyal to the regime that had killed him. He said just enough in public to do his duty, to help impose Stalin’s will on his architectural colleagues and ensure his own reputation for reliable loyalty. In 1929, when the strikingly original winning design in a competition to build the Lenin Library was abruptly abandoned in favor of a piece of socialist realist architecture, it was Iofan the party deployed to endorse the decision at a public debate. He was prepared to put his talent at the service of the “leadership of the militant vanguard of the Soviet people’s struggle.”

Another of Iofan’s close friends was the charismatic theatre director and actor Solomon Mikhoels, a kind of Soviet counterpart to Laurence Olivier. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the two men were founder members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee; Mikhoels became the committee chairman, touring the world to raise money and support for the USSR. After the war, when Mikhoels had outlived his usefulness, Stalin had him secretly murdered as a first step towards dismantling the committee. Before the majority of the committee’s members were arrested, Iofan was proposed by the NKVD (the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) as a more reliable replacement to take over the leadership. And in the course of his career he also worked closely with the three most fearsome leaders of the Soviet secret police: first Feliks Dzerzhinsky, then Genrikh Yagoda and finally Lavrenty Beria.

While none of the characters in “The House on the Embankment” is based directly on Iofan, the book vividly describes the milieu in which he and his family lived. It depicts the building in its pomp during the 1930s, when its residents enjoyed luxuries hard to find in Moscow. Iofan designed a hair salon for their exclusive use; a department store, stocked with imported items unobtainable elsewhere in Russia; a laundry; a billiard hall. There were home film shows, and there was a remarkable abundance of food. Even in the midst of the catastrophic man-made famine in Ukraine, which touched the whole country, the comfortable matrons of the House on the Embankment could afford to dismiss day-old cake as “stale.”

In 1941, Iofan led a team of architects and artists whose task was to camouflage sites such as the Kremlin, Red Square and the Bolshoi Theatre in order to screen them from German bombing raids. But, as Trifonov writes, “there was no way to disguise the river; its shining surface reflected the stars, its bends marked out the districts of the city.” Trifonov wrote about “cold, clear, starlit nights” when “anti-aircraft guns flashed incessantly all around and deafened us with their noise. I shall never forget that smell of powder smoke above the roofs of Moscow, the clatter of shell splinters falling on sheet iron and the sad smell of burning coming from somewhere beyond Serpukhovskaya Street.” The House on the Embankment “was surrounded by near misses.” Iofan and his family experienced for themselves the chaos of being evacuated, as portrayed in Trifonov’s book: “The evacuation trains left at dawn, but they had to go to the station hours beforehand because the business of getting on the train was so chaotic.” Iofan was one of the few who not only survived Stalin’s purges, but subsequently returned to Moscow — although, as Trifonov describes it, the House on the Embankment was never quite the same after the war.

Through a mixture of luck, judgment and calculation, Iofan stayed alive while many of his friends and colleagues did not. Trifonov too was able to negotiate his own accommodation with the regime, although he was one of only seven out of more than 7,000 Writers’ Union members to protest at the expulsion of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Georgi Markov, secretary of the union, rebuked him: “No matter how great a talent a writer may possess, it can be expressed with full clarity only in an atmosphere of struggle for implementing the great social transformation that is waged by the Soviet people led by its militant vanguard, the Communist Party.”

Through a mixture of luck, judgment and calculation, Iofan stayed alive while many of his friends and colleagues did not.

Yet Trifonov managed to get his book published uncensored in the Soviet Union — far from a given in the repressive Brezhnev era. He used his good fortune to present a nuanced but unflinching exploration of the choices that are open to individuals faced with dangerous moral dilemmas. His courage and the quality of his writing would have made him a strong contender for the 1981 Nobel Prize. “The House on the Embankment” is impressive both as a work of literature and as a reflection of its author’s integrity.

When Iofan intervened on the side of conservatism in the argument over the Lenin Library, his bolder colleagues were able to point to the modernism of his own design for the Barvikha sanatorium to suggest, at the very least, a certain inconsistency. Classicism had been a lifelong inspiration to him, but he was clearly also ready to work in other architectural languages. What, then, did Iofan really believe? To what extent were his stated architectural opinions based on conviction rather than expediency? There are some clues. Isaak Eigel, a former office manager in Iofan’s studio, published a monograph on his employer and friend in 1978, although his personal recollections may not all be strictly accurate — and he was writing at a time when it was not possible to be entirely frank. Iofan himself wrote a number of articles for the Soviet press, both professional and general. In addition, Moscow’s Shchusev Museum of Architecture holds many of his drawings and some of his correspondence, and there are more drawings in Berlin at the Tchoban Foundation.

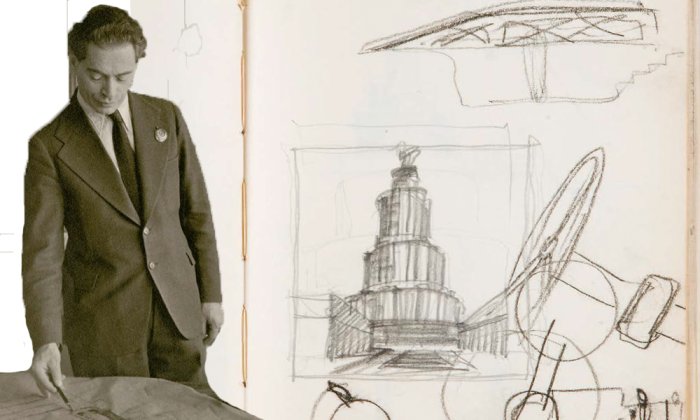

I was fortunate enough to be able to view some of Iofan’s hardback sketchbooks in the Alex Lachmann collection, with soft, yellowing cartridge paper and sewn bindings. He bought them in Paris and New York, along with the wire-bound ruled exercise books in which he drafted his speeches. The drawings especially seemed to offer a way into his mind: for an architect, it is much harder to conceal feelings in a drawing than in a safely typed sentence. These drawings trace Iofan’s development all the way from his ten years of studying and working in Rome to the building of the light-filled sanatorium in Moscow’s greenest suburb, Barvikha, and then on to the Palace of the Soviets and his other unbuilt projects.

The Barvikha project appears as humane and progressive as anything that Alvar Aalto — born seven years after Iofan and, like him, once a subject of the Russian empire — was creating at the same time in Finland. Patients at Barvikha even had rooms to themselves, whereas in the tuberculosis sanatorium Aalto designed at Paimio there were two beds in every room. However, Paimio was open to all Finnish citizens, while Barvikha was reserved for the hierarchy of the Communist Party leadership.

Barvikha and the House on the Embankment are clearly part of mainstream European modernism, whereas Iofan had previously designed modestly scaled, ingeniously planned apartment buildings in a kind of Mediterranean vernacular. After his first trip to New York in 1934 — despite the harsh judgments on American architecture that he later shared with Sgovio — he returned fascinated by Rockefeller Center, and its influence is visible in his design for the Soviet pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition. But none of these things would in any way predict the scale and form of the Palace of the Soviets, Iofan’s materialization of Stalin’s monstrous id. As Frank Lloyd Wright wrote of it: “The Work Palace, to be the crowning glory of the new [Moscow] construction, suffers likewise from grandomania of the American type in imitating skyscraper effects way up to the soles of the enormous shoes of Lenin, where the realistic figure of that human giant begins to be 300 feet tall. Something peculiar to the present cultural state of the Soviet is to be seen in the sharp contrast between thick shoes and workman’s clothes and skyscraper elegances. Lenin, enormous, treads upon the whole, regardless. Nothing more incongruous could be conceived and I believe nothing more distasteful to the great man Lenin.”

Iofan made his mark at three particularly significant moments in the political history of 20th-century architecture — in Moscow, Paris, and New York. Conventional accounts concentrate on the other participants in these cultural and political dramas: Le Corbusier, typically presented as the dominant figure in the 1931 competition to build the Palace of the Soviets; then, four years later, Picasso, whose Guernica was painted for the Spanish pavilion at the Paris Exposition; and lastly, at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Wallace Harrison with his Trylon and Perisphere and Norman Bel Geddes with his crowd-pleasing Futurama exhibit. But it was Iofan whom Joseph Stalin chose to design the Palace of the Soviets, rather than Le Corbusier, and the evidence shows that Iofan carried out his instructions faithfully. It was Iofan’s Soviet pavilion that confronted its German counterpart at the Paris Exposition, and it was Iofan who gave the Soviet Union the most popular foreign pavilion at the New York World’s Fair.

Iofan’s story is partly about his remarkable ability to survive the worst of times when many of his contemporaries did not, but it also illustrates the price of working for the monstrous Stalin. Iofan’s career is a precise reflection of all the compromises that architects must make with power. We should be thankful that for the past half-century, most creative individuals have not had to face such a brutally sharp choice. But with a disturbing increase in the number of leaders we can only describe as authoritarian — trying on the second-hand trappings of totalitarianism for size — now is the time to explore how previous generations such as Iofan’s addressed, or failed to address, these life-or-death decisions.

Deyan Sudjic, former Director of the Design Museum in London and architecture critic for the Observer, is the author of, among other books, “Stalin’s Architect,” from which this article is excerpted.